they will keep speaking the night

edited by Rob Budde. Prince George: Wink Books (at the UNBC Copy Centre), 2019. 28 pp. $10.00.

This chapbook, containing the work of fourteen poets, begins with a quotation from Wong, “jail the stories & the storytellers, but they will keep speaking the night, until empire expires.” This is followed by an appeal from University of Northern British Columbia professor Rob Budde, representing FightC PG and Sea2Sands, two advocacy organizations based at the university:

Dear Rita Wong supporters and Water Protectors: This is a fundraising chapbook “Keep Speaking the Night” in honour and support of Rita Wong who was sentenced to 28 days in jail for standing up to industry and protecting water, land, and Indigenous rights. In solidarity, FightC Prince George and Sea2Sands has organized the printing of a limited-edition chapbook, selling them to raise funds for Mountain Protectors, an organization Rita endorses now that her fines have been covered. This is for Rita and all those on the frontlines who keep speaking.

I have to start this review by pointing out that speaking is one thing, poetry another. Poetry written in the name of a cause, sometimes called (dismissively) protest poetry, can be objectionable if the poetry is used as a bullhorn and so lacks any personality — sensitivity to the issue at hand. There is a tendency these days to foster and teach the writing of poetry as message — especially in the schools and universities where poetry is taught as a thematic utterance, either in the older Arnoldian sense as the epitome of clear (read liberal) thinking or the newer post-colonialist sense as the expression of marginal (read oppressed) sensibility.

The problem with this is stated by Canada’s predominant theorist, Northrop Frye:

However useful literature may be in improving one’s imagination or vocabulary, it would be the wildest kind of pedantry to use it directly as a guide to life . . . . The poet is not only very seldom a person one would turn to for insight into the state of the world, but often seems more gullible and simple-minded than the rest of us.

Frye goes on to say that if you pulled messages out of T.S. Eliot, you might end up believing that all the problems of the world would be solved if everyone worshipped at the Anglican Church. Pound might convince you that fascism is the way to go, etc.

Fortunately most of the poets in this book avoid the bullhorn approach. Like Eliot and Pound, they clearly have a cause, but they don’t simplify issues, and they provide a personal perspective. Pound could write “Usura,” a poem that can be read as an attack on capitalism rather than a list of the problems created by sale of money as a product rather than its use as a medium of exchange. Eliot could write “Gerontion,” that can be read as a racist list of immigrants (starting with a Jew) draining the vitality of the West rather than an expression of the psychology of liberalism. Similarly, Wilfred Owen could protest war in poetry that is entirely experiential and that even entertains the idea that something that can inspire such great poetry can’t be all bad. Even Canada’s Tom Wayman, who advertises himself as “the people’s poet” and is capable of atrocities like “The Face of Jack Munro,” can rise above protest and write entirely sensitive and gripping accounts of life on the assembly or picket line.

Stephen Collis begins his poem by quoting Wong in the first line:

It became necessary to act . . .”

He repeats this first line in every subsequent stanza in the poem. In the second stanza:

It became necessary to act

We could imagine seas

Over our eyes but machines

Made it real for greed and gas

Of rob mclennan’s “Four poems for Rita Wong,” numbers two and three are most specific and suggestive, number 1 and 4 abstract and vague. Two and three can be read together as a continuous thought.

2. . . Deforestation, reigns. A tool

sits coolly in the earth: misplaced,

ten thousand lunar cycles. How can we live

if all else dies?

3. . . They can’t take it with them,

I guess. The world’s lungs

fill up with smoke.

Poem 4, however, does provide some specific background, referring to Wong’s jailing:

The contempt

is obvious. You resist, for ecological health

and mutual respect, and in response, they place

you

in a cold, dark room . . . .

Erina Harris draws on the treasury of the classics in her poem, “LETTER R – RESPONSIBLE: Excerpt from ‘Persephone’s Abecedarium: An Alphabet Play (An Ecopoetical Adaptation of the Homeric ‘Hymn to Demeter'” It invokes a fairy-tale winter scene and much mystery:

When the bad man stands on the white carpet.

When he asks the white and then you’re bad.’

Then the time is back for, I don’t know.

Man in the hat wants to be the Queen,

Inside the was he is asking me:

Eat her face or white or else, tomorrow!

Then I feed him . . . .

The final end note explains that “this constraint-inspired experiment borrows from the poetic and anarchic language-forms of infants and children, in search of what early articulations of the evolving self or ‘I,’ prior to full inculcation into anthropocentrism and patriarchy, might tell us about possibility: What other linguistic conceptions of selfhood are possible in terms of relationships with cultural others, animals, and things.”

This is, I think, an interesting if possibly delusional explanation of a good poem.

Erin Bauman, known as The Panoptical Poet and frequently host of ‘Word Play’ at Cafe Voltaire in Prince George, refers, in “Beyond Bread and Roses,” to the difficult cultural landscape in which Wong tries to deliver her ecological message:

A quick scroll through Facebook will give you the names

of at least a dozen missing Indigenous women

on any given day.

The fact that you CAN now read about them is

progress—

Proof that Kkkanada can’t keep all of its dirty little

secrets

no matter how much money

SNC Lavalin funnels towards the Trudeau government—

but one more missing

is one too many.

She incorporates some of her personal experiences into the picture she paints:

Screams from a white woman trying

to save herself from assailants

while out for a morning walk

are also a call left unanswered by the friendly

neighbourhood RCMP.

They are too busy sending SWAT teams

to the Unisto’ot’en Camp . . . .

This poem has its moments, but gets too close to the bullhorn for my taste:

We must take back more than the night;

ensure that immigrant children never again live in cage,

and that when cage doors do open

there is a world for us ALL to go back to.

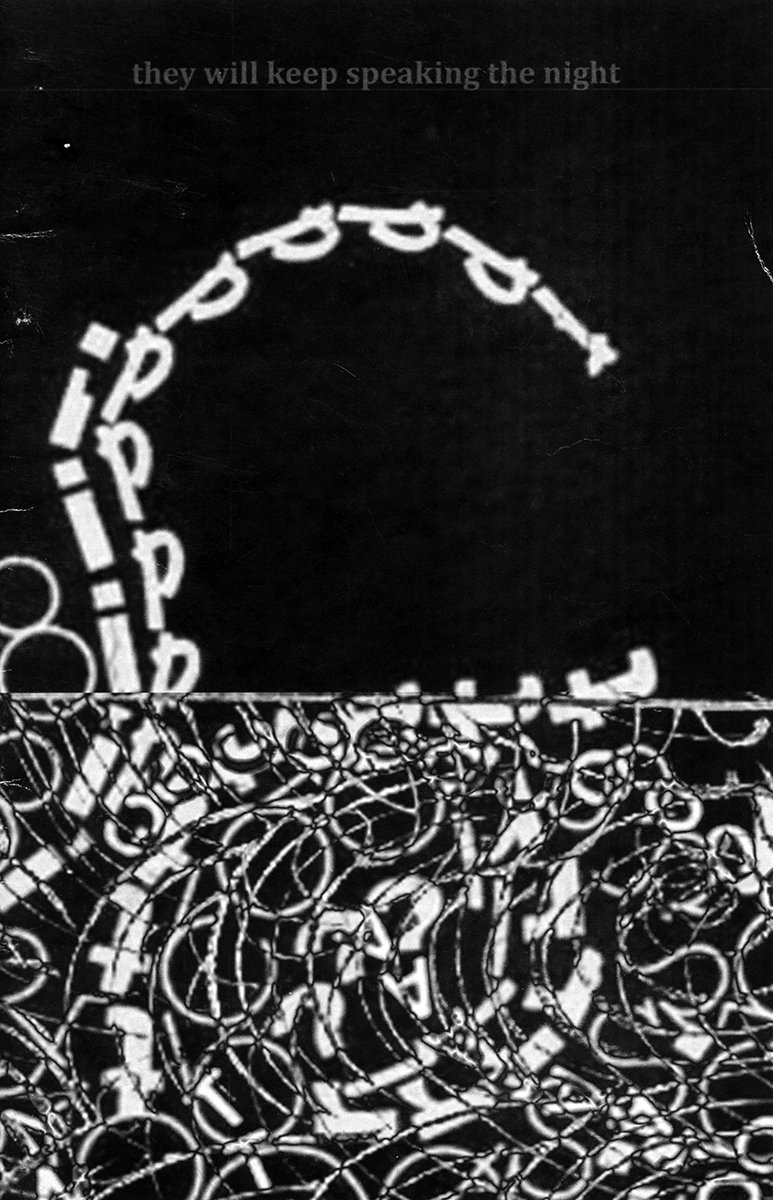

Art work by Gary Barwin includes “Two Water Sigils for Rita Wong.” Barwin has also collaborated with Derek Beaulieu in creating the cover art for this chapbook, a picture entitled “Net.” “Net” is also shown full-size in the middle of the collection after poems by Robie Liscomb.

“Offering,” by Maureen Scott Harris, is a tribute to Wong’s own poetry in the form of a borrowing of “touchstones:”

wanting to speak I reach for her poems

find touchstones, words I pillage for this

watershed moment as the jailed storyteller’s

truth-telling carries me into the now

where I seek fluid wisdom

to absorb the trickledrown of fear

surrendering it to groundwater

knowledge of the soil’s transforming power

The visual imagination of Kyle Bladow is evident in his poem, “Last Days”:

. . . Brush is stacked against the horizon

in brittle white filaments, sentinels

with ranks ablight. Grown unordered,

they press close around downed aircraft

and fall upon the power lines.

Robie Liscomb, in “prologue to another time,” refers to conditions in a minimum security prison and considers the interweaving of the present and the future:

. . . so you make space of dream and

breath of story and what music

wells up from the earth or such thin air

as hope has become

to restore a future world

and find our proper place in its

event the myth of its emergence.

In her second poem in the chapbook, “lines to keep me going,” Liscomb emphasizes suffering and compassion:

. . . the condition of suffering

the necessity of

love, compassion

as we enact

within this very existence

the world to come.

In “no mountain is safe” Ursula Vaira condemns mountaintop removal as a means of mining coal:

. . . no mountain is safe now

we stand

blinking

at the sudden light

Jonathan Skinner, in “We Care About Your Privacy,” mocks the cliché’d assurances of safety and respect offered by our social superiors:

. . . The poem will always beat enclosure

Train up your memory, poets, for the day you will be jailed when they confiscate your pencil

memory plus anarchy is a conditional future. There is no private account, no public without us

the arch present’s funeral is the presence of tomorrow. The masses are coming . . . .

Unfortunately, Skinner counters these cliché’s with others concerning the “solidarity” of the “masses,” “mask of philanthropy,” “moth [moss?] and rust of your terrestrial kingdom. Slinging clichés at other clichés is depressingly journalistic.

A gem in this chapbook is Laiwan’s “Poem #17 for Day #17 for Rita Wong.” It is a complex, multi-layered poem inviting interpretation on many levels:

It was when a queen’s engineer

decided that the river over-meandered

causing the fall of the western empire

into a perfection of straight lines

. . . . What engineering will we need to make us again meander?

Jessica Cory’s “Flash Flood Warning, Haywood County,” is a sonnet with a Shakespearean rhyme scheme, and shows technical mastery in its muted rhyme and meter. The second stanza is representative:

the neighbors’ aging car

perched on its cement blocks.

Another drives just far

enough in for the brakes to lock.

The ending couplet is wonderfully imaginative:

As the waters rise, they also drown

everything in salamander brown.

The collection ends with “Enough,” by Steffi Tady. The poem derives its themes in part from Ontario indigenous culture:

Surrounded by the sound of blue falling, an uncle

& his niece in Haudenosaunee, Ojibway Territories

watched the Maiden of the Mist tear across the

water unknowing of the border. . . .

They listen to what is quelched, recover what is

squashed, give value to what is commodified, the

way they offer you water and food to eat, is in and

of itself an indictment of greed and empire.

While I don’t care for some of it, the chapbook is a weathervane of our times, and a cultural barometer. It will be an important addition to a library of contemporary poetry. I recommend that you buy it, whether you support Wong’s cause or not. The poetry is worth supporting.