Barry McKinnon & Cecil Giscombe Literary Reading

The unrestricted literary imagination was at play during the readings by Barry McKinnon and Cecil Giscombe held at the Black Donkey Café on June 10th. The atmosphere lent itself well to free-thinking and the strengthening of friendship.

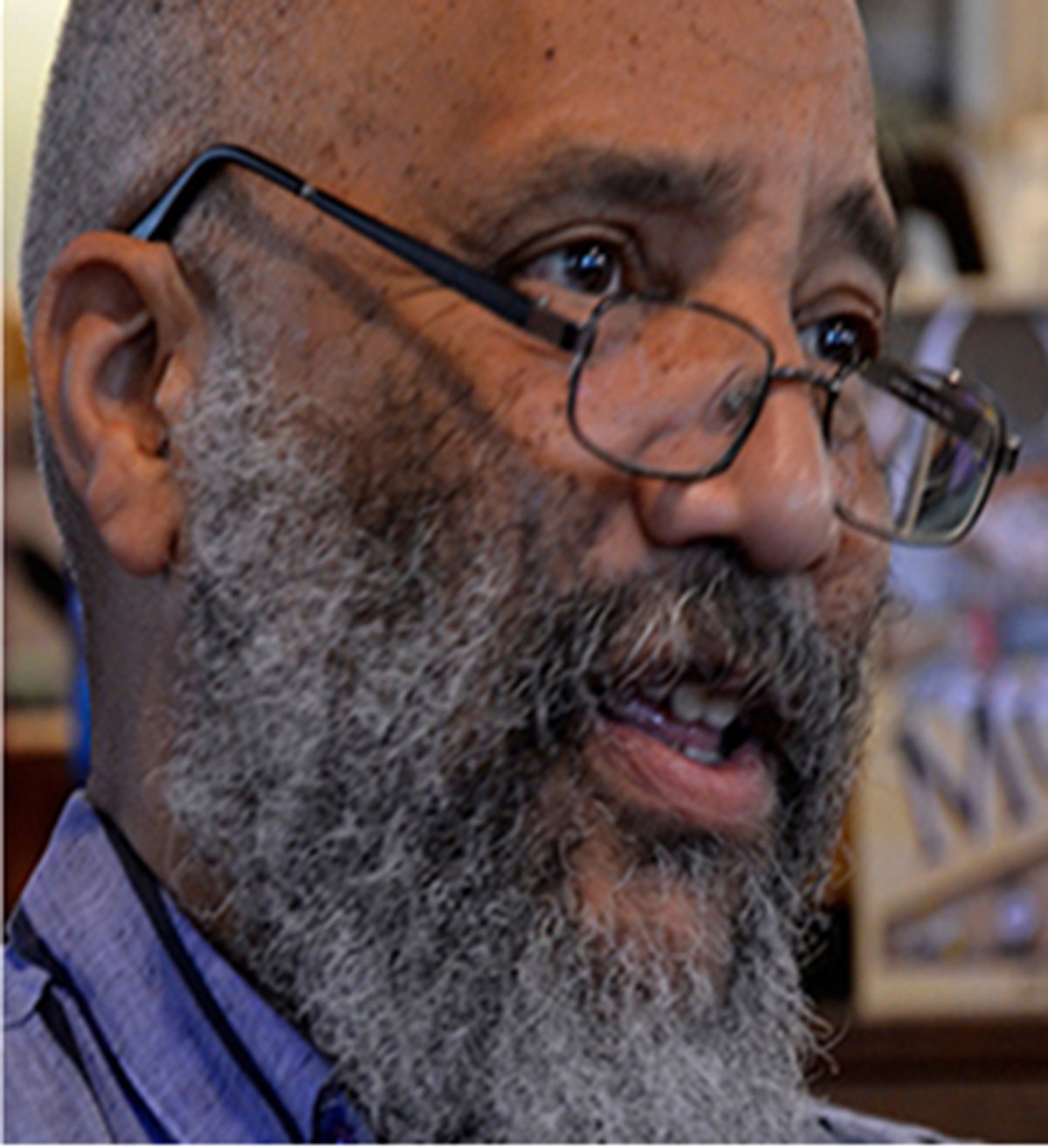

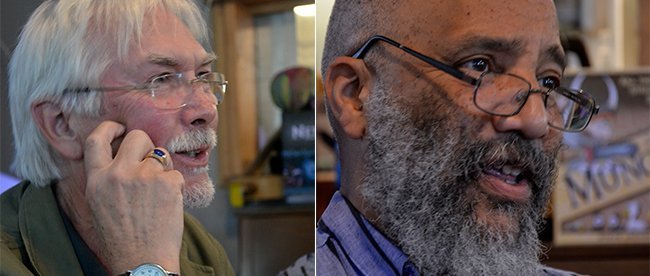

John Harris introduced the two poets, Barry McKinnon of Prince George and Cecil Giscombe of Berkeley, California. “I like what they’re talking about – serious issues,” Harris said.

Harris referred to McKinnon’s strong interest in the American poet Robert Creeley (1926-2005) and the Black Mountain school of poetry and literary thought, as well as in the Connecticut Modernist poet, Wallace Stevens (1877-1955). Harris briefly mentioned Stevens’ 1942 poem, “The Man on the Dump,” in connection with the subjects McKinnon brings up in his poetry, written in an industrial town frequently unfriendly to literary creativity.

“Now Prince George is not a garbage dump,” Harris continued. “In fact, it’s a beautiful place, but people don’t stop here or take tour buses through here.

“Barry’s very good at metaphor,” Harris added. “The thing about metaphor is, it’s not reality, but refers to it.” In his book of poetry, The the, McKinnon says we’re avoiding reality, Harris noted.

“Barry got into trouble for what he wrote about Prince George, and the endured criticism of his pioneer family [described in his 1990 poetry collection, “I Wanted to Say Something.”]

“I got into writing the long poem around 1971,” McKinnon said at the beginning of his first reading. “Now people can’t handle the length. Maybe I should write haiku.”

After he read “Astoria,” about an incident in a Prince George pub that illuminated life in the city, he read from “Radio On” in his 2009 book, In the Millennium: “Radio on, thinking I’ll write a story about gardening for Stan Chung – on George Bowering . . . .

. . . though the sun is high, bright and beautiful, but you must

constantly think, stink of polluted air. perhaps there is no hope.

(yet live daily &

sing the body

electric

Turning to the poem “Bolivia/Peru,” also included In the Millennium, McKinnon described a breathtaking trip in the Andes from Bolivia to Lima, Peru, but the pleasure of the journey was seriously marred by a mugging in the Peruvian capital.

(robber grabs purse, flash of red, no face / body – Joy screaming

my name – clutches purse to chest, then flipped / back to the

ground dragged in / along street. guy won’t let go . . .

McKinnon successfully fights off the robbers.

. . . Joy OK – bruised my wrists hurt elbow bleeding long scratch on leg.

duck into first safe-looking

restaurant. drink 2 beers. in shock – get safe taxi out. Remember sympathetic waiter in Spanish sd: in life there is good, there is bad.

Cecil Giscombe, who teaches English at the University of California-Berkeley, described how his African-American ancestor, John R. Giscome, arrived in northern B.C. in 1863. Giscome Portage is named after him. Cecil Giscombe has been visiting and staying in Prince George at intervals since 1995. “His father is a doctor and his grandfather was a doctor,” Harris said in his introduction.

“There is much symbolism here,” he said.

“I have a bit of a railroad past,” Giscombe continued. “Railroads are interesting. Trains are hugely sexual. I’ve worked on the margins of the railroad industry, which is very hierarchical.”

He read “Two Pieces Having to Do with British Columbia,” from his collection Railroad Sense, including the following excerpts:

“I’d dreamed on more than one occasion of encountering wolves at Isle Pierre, thirty miles to the west of Prince George, before I remembered or connected the dreams to the fact that I did see, in my waking life, the only wild wolf I’ve ever seen, at Isle Pierre in the 1990s. The dreams were sentimental, I saw then. I had seen the wolf from the Yellowhead highway, which parallels the railroad much of the way from Prince Rupert to Jasper, and I wrote about the sighting. “Crazy on You” – the popular song by Heart – had been playing on the car radio and I’d described it as “trashy rock and roll,” as “a song we all half knew.” But twenty years later, when I watched Heart’s introduction to the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame on HBO the two sisters who were the core of the band, Ann and Nancy Wilson, played the song with some gusto and I said aloud, in my home in Berkeley, California, “wolf music” . . . .

“ . . . To a friend (Miss Maria Whitney) Emily Dickinson wrote, ‘The ravenousness of fondness is best disclosed by children. . . . Is there not a sweet wolf within us that demands its food?’

“Later in the HBO program Harry Belafonte introduced Public Enemy. People were beginning to talk then, in 2013, about the sheer numbers of young men of color who were in prison in the United States. As part of his induction statement Harry Belafonte asked for the power of President Obama’s heart to ‘correct these hideous abuses of jurisprudence and address the inequities of this war on our children.”

Giscombe also read from “East Line,” also from Railroad Sense, an account of a day in 2009 spent out on the East Line with Prince George friends. “There was such a silence between the East Line towns which no one could describe and in which anything could happen, or so it seemed to me; the silence, I thought, was traced by the railroad, which was often invisible from the road – Upper Fraser Road – that we were traveling on. The road was paved but so few people lived on it that we encountered only three or four other cars or trucks as we traveled. I had remarked on this before, had ‘spoken’ of it – the silence—in print, so I was not surprised by this particular Sunday. That is, I recognized it. . . .”

In addition, Giscombe read from a project called ‘Distance’: “Still taking multi-day, unsupported cycling trips. Camping, cheap motels. These are haibuns. Cross-genre form combining prose and haiku. . . .

“Nothing comes from nowhere. . . .

“First Montreal Tour: . . .Crisp October Days, 1980. . . . Observed that everything translates into known quantities or what one knows of quantities – noted as I went further in the trip itself that because I had no familiarity with or even particular knowledge of the territory I fell back on the fact of distance, how I knew, say, what ten miles was. . . . A child’s voice taunted me with a cliché concerning death and seasons, an ‘auditory hallucination’ .…”

Giscombe also read from an account of a bike trip from Oxford to Bangor, in Wales, in June 1987. “I trailed a slow-moving train on the way to Bangor, keeping just behind it, coming again and again to stretches of wet pavement. I tried to call home – Oxford then – from Chipping Campden but the line was ‘engaged.’ Graham Greene wrote Stamboul Train in Chipping Campden. The whole island was a verdant suburb. I’d come to Long Compton with a man and a woman I’d met, all of us on bicycles, and we stopped at her house for tea in the garden. The man was a flautist. She sang part of an old song about six witches on a hay cart on Long Compton Hill. I found hostelry in Broadway and in the morning, from the kitchen, Joan Baez sang ‘Farewell, Angelina’ on the radio. ‘I’m going all the way,’ Greene had had Coral Musker say, meaning Istanbul. Then more rain came . . . ”

At the beginning of his second reading that night, McKinnon noted Joy and he had been going to California for the winter for the past three to four years. “I’ve been falling in love with the desert.”

McKinnon observed that when it’s -30º in northern B.C., you can die if you walk outside in casual clothing for more than twenty minutes. In the far southeastern California desert, a similar short time in desert heat can be serious or fatal because it’s too hot. “It can be 130º in the summer.”

He read from his poem “Slab City,” from his collection Gone South, about a desert community along the Salton Sea near the Mexican border:

— “freedom” (unquote – is tolerance? or so I thot

in — Slab City (in the range of

outliers, hobos, patriots, artists, tourists, military guys

in camo, snowbirds, the neo whats? Thus the guns, blasts at night into

the dark, hot, air.

no sense we’re not there or welcome /to a measure of who

we are – drawn to some sense of the end of the earth & its ragged (rigged?community

a language / human typos . . . .

poverty – the hell of any desert

Paul: it’s all blue man sky and sea yes! Yes! — colours/the primary desert

In the desert morning heat

. . .

what is reality? only the figment of the imagination as it seeks itself? The

Slab: simpler? or

more complex than what sociology I can muster. Degrees of heat/the

diminishment/measure

. . . the noise of guns & traffic – the great

rooster Fog/Dog horn who wakes us/ then barking dogs, then gas engines, then human

clanking. the sun is up!

do people die here? I’ve heard ambulances at night. . . .

One thinks of claustrophobia, or the Eagles song “Hotel California,” or the motor home scenes in the movie Independence Day. McKinnon’s Poem continues:

at the Slab, no escape of . . . exit is also entrance? “reality” ahead. It was is a sense

simultaneous that no one connects thus becomes connection – thus the

attempt all the more/to

sense the blue, dark, wordless desert, the disparate selves gathered here.

McKinnon jokingly referred to an imaginary satirical Prince George writer, Jack Daw, who moved to New York and knows five different languages, and who takes up topics like “trans-transnational meta-text.” Daw lampoons foreign curses in English idiom.

“The guy’s brilliant!” McKinnon said at the end of his second reading of the night.

Giscombe began his second reading with “Three for Tom Merwin,” from Negro Mountain, so named for an eighteenth-century clash involving colonists, First Nations and African-Americans. “Three for Tom Merwin” is divided into subsections titled “Upstate,” “Uptown,” and “Downtown” – references, respectively, to northern New York State and to different sections of New York City.

Upstate

Ambiguous siting, dear friend, and lousy

with poets. No wonder you decamped for New York! Compare

or contrast imaginations in which I became a priest! Tug

Hill! We’re all innovative, they said . . . .

The second subsection, “2. Uptown,” proceeds at a different pace:

acting the fool over deaths from a different scale or vernacular. Tsk-tsking

permission, the green man arches his brow. Fire up on the West Side, say at

Hundred/ and Seventh Street, and you and Gus and Ellen and I watched,

looking in – as / it were – from Broadway. In the shower of sparks kindness

is easy / to call in or limit – watch for me by firelight, darling. It’s / true but

it’s a fact, something I knew about. Only one/truck . . . .

too hot for poems, the scene was ghastly quiet. Taxicabs whizzed by behind us . . .

The third subsection, “3. Downtown?”, creates unease:

Unsure of what question to ask when we – Ellen

sitting between us – were at the bar at Peter McManus’s. Big fellow came

into the subway car, you said, punching the windows ‘til

they broke, girlfriend or wife or it might have even been his sister holding

on to his

back, riding him down the aisle, as it were, yelling Stop. But the

average person in

New York, you said, is happier than the average person Upstate. . . .

Later I wondered, how far

were we – in “functional downtown,” in this mess – from Negro

Mountain? Weather

came

over the mountain as we do. Oh boy, dear

friend, oh boy, oh boy.

About twenty-five people attended the event, which was well covered by photojournalists. At the conclusion of the reading, everyone adjourned to The Black Clover two-and-a-half blocks away to discuss freedom of the imagination and literary creativity.