Fanny Price’s Question

I’m a big fan of the Times Literary Supplement that, no longer content to be associated in the public mind with a periodical focused on ephemera (news and public opinion), now calls itself by its acronym alone: TLS. For us bespectacled eggheads with an obsession with books, a love of elegant prose, and an intimate knowledge of and reverence for the English literary canon, TLS is the magazine of choice. It feeds our bibliophilic passion with analytical and evaluate essays and reviews, but also caters to our sense of solidarity and élan in the face of the decline of public literacy. It teases us with pun-y titles, literary crossword puzzles, tours of used-book stores that focus as much on the eccentricities of their lovable owners as the treasures found on their shelves. TLS editorials feature self-reflective comments on the peccadillos of other literary magazines, everything from their typos to their ridiculously inflated statements of editorial intent. I was especially happy awhile back to clip the useful “Hackneyed Handbook,” informing me, for example, that when things are ‘few’ they are also, and much too often, “far between.” Not only that, but “bedfellows” are, too predictably, “strange.” Finally, there are letters to the editor, wherein nerds like me can chime in with our own commentary on the great questions, like whether or not Beowulf was celibate.

TLS is a yearly gift from my wife, starting on my 63rd birthday in 2005, the year I retired from my job as a college English instructor. It was a thoughtful gift, akin to allowing a bookworm into the Vatican Library. It benefitted her too, by keeping me out of her hair most afternoons (in the mornings, I work on my poetry) and, most evenings, by guaranteeing her control of the TV remote. But 15 years of post-retirement connubial bliss was threatened by an editorial by Martin Ivens, a hale fellow, in number 6141 (21 May 2021). This editorial informed me that, in the featured article by Devoney Looser, I would learn more about Jane Austen’s family connections to slavery.

Great! I thought. TLS dishes out a good deal of tabloid-style trivia about the canonized, as a kind of comic seasoning to our community worship. “Jane dates slave!” But when Ivens suggested, about Jane’s father George, that he would have had “qualms” about being, at one time, “co-trustee for a marriage settlement financed by slavery,” I smelled something off.

Why would George have qualms about forwarding a marriage settlement for a plantation-owning friend, any more than I’d have qualms about answering my cellphone, powered by batteries made safe for me by the cobalt mined by child labourers in the Congo, some under six years of age and many dying of suffocation in the un-braced tunnels, or suffering the effects of heavy-metal blood poisoning for the rest of their foreshortened lives? Or putting on a shirt manufactured by indentured garment workers in Bangladesh, women who work twelve hours per day for a pittance and die by the thousands in factory fires? Or eating a yam (roasted with brown sugar!) produced by underpaid immigrant farmworkers from El Salvador, who are housed in cramped quarters and poorly fed, and have no workmen’s compensation or health insurance? Or (finally) turning on my fireplace (beside which I read TLS) fuelled by natural gas produced by fracking that pollutes the well water and streams on unceded aboriginal land?

Did George Austen have qualms because he was balmy — a fact that might explain Sir Bertram and some of the other patriarchs in Jane’s novels? Or had Ivens been swept up in the Black Lives Matter movement and / or campus postcolonialism, joining a herd of lemming-like professors and students intent on defacing the entrance of the Jane Austen Museum in Chawton with hateful graffiti?

I read on into Looser’s “Breaking the Silence: The Austen Family’s Complex Entanglement with Slavery,” only to find my worst fears justified. In her article, Looser presents the results of her research into the Jane Austen family’s involvement with the West-Indies, sugar-plantation, slave economy. Her research springs from the one allusion to slavery in all of Austen’s novels. In Mansfield Park, Fanny Price mentions asking her uncle Sir Bertram about the slave trade in the West Indies, where he owns an estate. He is pleasantly open to her question, and she reports getting an answer from him, but she doesn’t repeat or summarize either her question or his answer. She implies that the frigid silence of her cousins, who brook no conversation that is not frivolous or about themselves, forced her and her uncle to change the subject.

Looser mentions that Edward Said made much of this scene in Culture and Imperialism (1993). Based on a misunderstanding of what Fanny said, assuming the silence was Sir Bertram’s, he argued that slavery was the “dark underbelly” of the novel. Said is famous for inspiring the Foucauldian surge in postcolonialist criticism in the universities, though he ended up calling most of it stupid. Looser, in justifying her research, quotes a couple of postcolonialist scholars, Manu Samriti Chander (Rutgers) and Patricia A. Matthew (Montclair State), who live up to Said’s estimation by proclaiming that, “It should no longer be possible to read literary works from this period without attending to the geopolitics of slavery.”

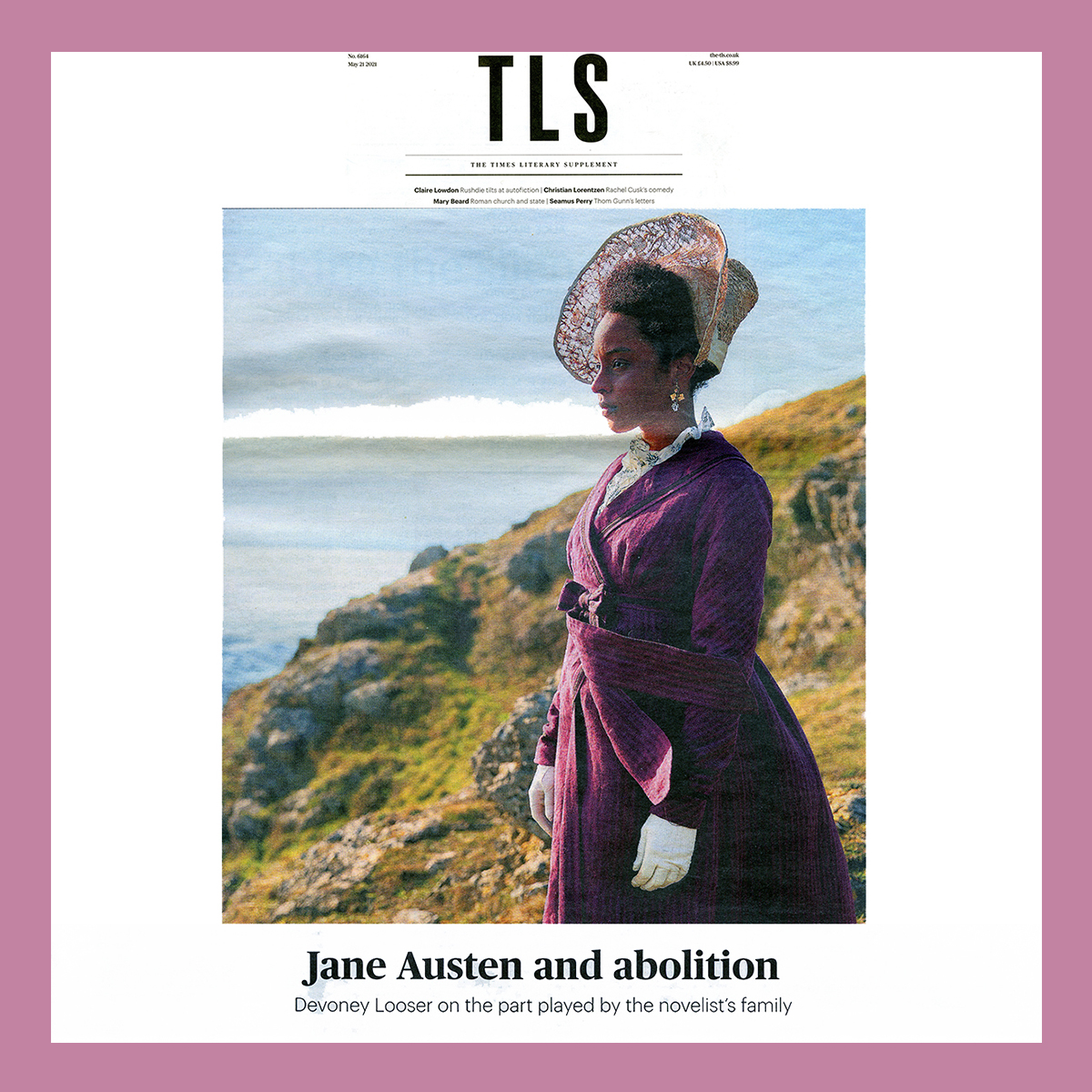

This meaningless statement, Looser claims, indicates why research into Austen and slavery is an urgent matter. Also contributing to this urgency is the increase in Austen spin-off movies that incorporate the theme of slavery, like the 1999 film version of Mansfield Park that adds dialogue and conflict directly connected to the fact of Sir Bertram’s plantation. Sandition (ITV 2019), an extrapolation of an unfinished novel by Austen, deals with race and slavery, as does the Regency-inspired Netflix series Bridgerton. The Jane Austen Museum, in April 2021, announced its plan “to educate visitors about the author’s connections to slavery.” The plan was said to be “just the start of a steady and considered process of historical interrogation.” The word “interrogation,” commonly used, along with the equally pretentious “intervention,” and the older “deconstruction,” to describe the analysis and evaluation of literary texts, was evidently being used now to indicate the museum’s re-appraisal of its artifacts and displays. It raised hackles with Jane Austen fans who imagined their icon strapped to a chair under glaring lights, being asked how many spoons of sugar she took in her tea, and exactly how many qualms she felt about it. The museum, Looser says, needed a more “layered and nuanced” approach, and this her research would provide.

The facts presented by Looser are as follows. The Austen family were friends of the family of James Nibbs, who owned a plantation. One of the Nibbs sons was taught by Jane’s father George in the family home, and George was co-trustee with one Morris Robinson in a marriage settlement that involved the dispersal of the Nibbs plantation assets. Of Austen’s two Royal Navy brothers, engaged in stopping the shipping of slaves on the high seas, one spoke privately against slavery. A third brother, James, represented Colchester at the 1840 World Slavery conference in London. There’s no record of him speaking at the conference, but the fact of his being there indicates that one member of the family took a public stand on the issue. Likely, his opinion was Jane’s; among her letters, there’s one that says she’s “much in love” with the prominent abolitionist Thomas Clarkson.

Looser advises us to stay tuned: “Those with expertise in English and Antiguan property law” might determine whether George Austen could be said to actually have run the estate for a time while facilitating the property transfer. This would, it seems, cause him to be viewed as an absentee overseer, holder of a remote whip. Or, more incriminating facts could come from George’s connection to co-trustee Morris Robinson. These facts “might expand the ways we imagine George Austen’s becoming a trustee for these complicit-in-slavery assets.” Robinson is also interesting in other connections: “He was the brother of Elizabeth Robinson Montagu, the so-called Queen of the Bluestockings, one of the most important figures in British women’s intellectual circles. (Mrs Montagu’s husband, meanwhile, was a wealthy coal mine owner.) George Austen’s connection to Morris Robinson through Nibbs may put Jane in closer social proximity to the Bluestocking Circle than has been formerly thought.”

Fascinating. But all of Looser’s historical details are trivia, since they concern Austen’s family, not her, since Austen’s novels are silent on slavery, and since we’ll never know what she thought of it beyond the probability that she was against it. The trivia is interesting, but comes at the heavy price of reading Looser’s mealy-mouthed insinuations that her research proves Austen’s “complicity” with slavery, and that readers need to wake up to that fact. Henry’s attendance at the anti-slavery conference becomes the single most important of her findings because it enables her to indict Austen’s novels. “One may rightly say that it took too long for someone in the Austen family to stake out such a public position.” (Note the “rightly” — Looser reaching around adverbially to pat herself on the back.) This must mean that Jane herself, older than Henry, and the only “someone” in the family of any importance, should have stepped up to the plate before he did. It must also mean that, since her novels represent her only access to the public, she should have staked out her position in them.

Readers generally assume that novels are written more for their entertainment than their enlightenment, but Looser and her colleagues Chander and Matthew assume otherwise. All three imply that responsible readers are obligated to bone up on the history of slavery during the regency because, “for those who might resist reading Jane Austen’s fiction in a political framework, these newly unearthed facts about her family ought to serve as a wake-up call.” Austen, as a novelist, needs to be called to account: “Scrutinizing the past in these ways ought to prompt a reckoning in fandoms and readerships, as well as better museum labels.”

No longer, apparently, can readers allow themselves to become thoughtlessly drawn into Austen’s illusive spell. They must be wary of her witty dialogue, her varied and colourful characters, her direct narrative style, her crystal-clear prose, and her stories wherein smart, attractive, honourable and economically insecure women catch the attention of smart, good-looking, honourable and economically secure men, come together with those men despite impediments thrown up by social convention and ridiculous and jealous people, and live happily ever after in a castle full of servants. These delights of Austen are meant to hide her characters’ complicity with slavery.

Instead of enjoying Austen, readers who obediently attended to the geopolitics of slavery would instead, I suppose, have to regard Austen as a mere writer of Harlequins, a spinner of wish-fulfilment dreams for the permanently infantile. Elizabeth Bennett, Austen’s most famous character, would be seen as smart but unaware of her complicity with slavery because focused on only herself. She is a snappy bitch, who fails to look into the source of Darcy’s immense fortune. As for Looser’s promised museum labels — how will they read? “Austen’s Wedgwood sugar bowl, filled with the blood, sweat and tears of slaves.” “Austen’s favourite raised-waist shift, made with materials produced by child labourers in Westmoreland textile factories.” “Austen’s reclining armchair, made of mahogany from the endangered carbon-sequestering forests of British Honduras.” And, on a portrait of George that no doubt hangs in a prominent place in the museum, a label stating “Austen’s beloved father, hypocrite pastor and overseer of sugar-plantation slaves.”

Looser and her colleagues are employed to teach young people to read and write, and reading for theme is the key to learning how to write. At the university level, this methodology is dignified by fancy words like poetics and theory, and these change over time depending on ideological shifts and intellectual fads: Arnoldian, Marxist, feminist, structuralist, post-structuralist, post-modern, post-colonialist. Each of these methodologies precludes the previous one, enabling professors to issue stirring calls for reform and ardent denunciations of the works of dead or retired colleagues, or those still fixated by the immediately previous fad. The ideologies are simplified for children and applied to the canon to locate “topics” for essays, theses, and exam questions: “Sexism in Shakespeare,” “Wordsworth as Philosopher,” “Austen as Racist.” Said, a professor of English at Columbia, was familiar with the process, and to some extent guilty of using it himself, as Christopher Hitchens pointed out. But he recognized its origins in credulity and professorial chicanery: “Literary criticism is essentially both religious — the model is commentary on sacred text — and so rarified and jargonistic that it’s just not interesting.”

Attacking a novel for what’s not in it is silly: the list of topics not in a novel is infinite. Arguing that the absence of something proves its presence is a favourite ploy of conspiracy theorists. It’s sad to see them operating behind a front of scholarship, sadder still to be reading their infantile nonsense in TLS.

Excellent commentary!

Yes, John, you have hit the preverbal nail on the head…in fact quite a few nails in that one. Good to see you are still sharp as a tack. I am trying to regain some of the tools I learned a long time ago. Should have taken one of your courses. I also finally figured out you must be 80 years old…just 4 years younger than me! Keep up the good work and say hi to the wife for me.

Beautifully written, thanks to both depth of knowledge (and research) and your welcome sense of humour. However, there is an underlying seriousness here, which is much appreciated. But, John, think of all those poor souls in search of topics for their dissertations, desperately seeking research funding. They need to come up with supposedly new perspectives to receive publishing credits and, eventually, tenure.

There is often need for a new look at old works; when I remember the ways in which Hemingway, Bellow, Updike etc. were presented when I was at university a million years ago, it was refreshing to read feminist critiques that echoed my own visceral response to them. Plus that feminist criticism meant we got to hear from women like Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, Doris Lessing (I’m showing my age), and Leslie Marmon Silko. They got published and put on the curriculum. But the direction Looser and others take kills the interest of those who just love to read great writing and mull over what it offers under their own terms.

Francisco Goldman wrote a memoir, Say Her Name, about his wife Aura Estrada, who died in 2007 in a bodysurfing accident in Mexico. In it, he talks about her move from Mexico to do her doctorate at Columbia University in Spanish literature only to be distressed at the lack of enthusiasm and affection for the literature itself in the program, how it was all about doctrine. Literary theory can be fascinating but to be of value, it must be layered within a love and careful reading of the works themselves.

Did you send this to the TLS?