Fawcett Memorial by John Harris

In Prince George, Brian Fawcett is considered royalty, a scion of the family that owns Kelson Group, one of the largest owners of rental property in western Canada. The company started here, and the town is thickly sprinkled with Kelson apartments. He is also the town’s most famous writer. Since much of his writing is about the town and its environs, and since his writing was published in the US and UK, his “take” on the place is prominent and unavoidable for anyone anywhere studying, and writing and talking, about Prince George — for academic historians and sociologists, for print and media journalists, for writers, and for teachers.

Brian was born here, and not many of its citizens since, including this writer, were. Arriving in a new place, we incipient locals necessarily spend a lot of time figuring out where we are and adapting accordingly. Brian provided for us a mythology that showed where and how we fit in, and how the town fits into the world. Brian’s take, put simply, is that Prince George, as a resource-extracting (furs, then trees) and primary-manufacturing (lumber and pulp) boom town, was created and shaped by technology-enhanced globalist capitalism.

In Prince George, the assault on nature is obvious: three pulp mills, their effluent pouring into the Fraser, the white cloud from their smokestacks permanent to the east, their stink everywhere. The Bowron Clearcut, just east of town, was created in a hurry and for good reason, to salvage thousands of acres of dead pine before they caught fire, and was big enough before it greened over to be seen from space. Williston Lake, to the north, was made to feed the Bennett Dam, and is the biggest lake in BC, its waters littered with driftwood from the drowned forest beneath. Giscome, once a sister-town 30 kilometers to the northeast, was reduced to a few acres of grown-over cellar holes and the concrete pilings of a gigantic lumber mill. Other disappeared or disappearing towns in the vicinity are Tumbler Ridge, Mackenzie, and Upper Fraser.

Similar phenomena exist in the much larger cities to the south, but are more out-of-sight, people there living and moving around in more specialized enclaves and less aware of the physical presence of industrial plants and the infrastructure that brings gas, oil, coal and lumber from the interior.

And everywhere in Prince George there are the displaced. Most of the citizens are from elsewhere, like me, and came here for jobs. Most leave on retirement or when the jobs end. The Carrier were ejected from Inginika, a village now under Williston Lake, and from the Fort George reserve — shipped upriver, only the graveyard left to remind citizens walking the town park. Hundreds of workers from town are bused to and from vast work camps — around the Site C Dam, along the route of the GasLink pipeline, two of the latest in a series of mega projects going back to the Grand Trunk Pacific, Alcan, the Bennett Dam, and Tumbler Ridge.

To figure out the effects of globalization on human nature, Brian read the journals of Mackenzie and Fraser, and went to the places where they crossed the divide between waters flowing to the Arctic and those to flowing to the Pacific. He wrote about what motivated these explorers and what they may have felt. He worked for legendary local entrepreneurs like Ben Ginter and his own father, and pondered their personal tragedies and the enigma of their ambition. He worked on the falsified surveys the BC Forest Service did to justify the flooding of thousands of hectares of prime timber in the building of the Bennett dam. He experienced, as a child, youth and man, the growing pains and pleasures of a boom town.

He returned to Prince George pretty much every year to check the town’s pulse, visiting old school-friends, joining the coffee-klatch discussions at the Simon Fraser Hotel of his father’s ageing colleagues and competitors, researching stories, and participating in the weird academic rituals of the college (1969-) and university (1992-): literary readings, creative writing classes, and academic conferences about poetics, local history, and postcolonialism.

Stan Persky, philosopher, publisher, journalist, fiction-writer, teacher and friend of Brian’s, explains how Brian’s mind worked. Brian’s, he says, is a “cosmopolitan intelligence” that “like all thinking, has ideological commitments, but is demarcated from fundamentalisms and totalitarianisms in that it does not view phenomena through an ideological lens. Rather it tests its beliefs through actual experiences.”

Brian’s actual experiences here and the stories he based on them did not mesh that well with other more institutional stories that discount individual experiences in favour of various fundamentalisms, totalitarianisms and ideologies, or in favour of chamber-of-commerce, city-hall, governmental, service-club and corporative boosterism. This didn’t bother Brian. He was the quintessential “bad boy,” always prying, always mouthing off, but his response to criticism and antagonism was basically civil. He referred to himself as a small “l” liberal. He incorporated criticism into his analysis.

And he knew that, while governments, companies, parties, educational institutions have a lot of control over what happens, the artist has a lot of control over how people come to understand what is happening. The arts are not celebratory of civilization, nor subversive, but contextualizing and corrective, urging the mind, as T. S. Eliot put it, “to aftersight and foresight.”

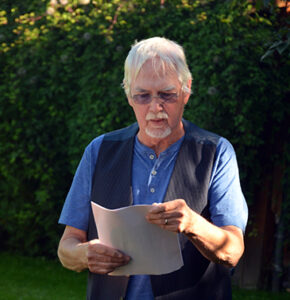

In the following piece, I wanted to show the specifics of how Prince George treated Brian. It was a love-hate relationship. I meant my study to be a part of a series of tributes to Brian, three of which (by Barry McKinnon, Paul Strickland and myself) already placed on this site. As it turned out, I also read the piece at a memorial to Brian instigated here in town by Brian’s two sons, Jessie and Max, and his daughter Hartley. The memorial accompanied their disposal of their father’s ashes as instructed by Brian, and was hosted by Barry and Joy McKinnon who, over some 50 years, were, like Persky, close collaborators.

After listening to some of the testimony at Brian’s Prince George memorial, my specifics about Brian’s presence in town now seem to me to be sketchy. But some of the other testimonies should appear shortly on this site to fill out the picture. Meanwhile, we are adding photos taken, by Vivien Lougheed, at the memorial. The names and captions might give our readers, especially those who know of and / or have read Brian, an impression of the stories that emerged.

Brian Fawcett in Prince George

1970 – 1980: Barry McKinnon and I teach the long poem Cottonwood Canyon in our poetry classes, and the short story Walking Cunt in our short-fiction classes. For this we are attacked by local members of the moral majority. In the mid 1970s, we published these in anthologies called The Pulp Mill Poetry and The Pulp Mill Prose. Because publication was funded by the Canada Council, which didn’t then ask for any accounting, we were able to give these books gratis to our students.

1980 – 2000: Barry and I, and then other members of our department like Don Precosky and Peter Maides, teach My Career with the Leafs, The Secret Journal of Alexander Mackenzie, and Cambodia to the students in the first-year fiction courses. Fortunately for us, the postcolonialists up at the University of Northern BC, who replaced the moral majority in our lives, don’t get wind of this before the books go out of print. Brian thanks us for keeping the books in print far longer than they normally would have been.

Don Precosky

Peter Maides

1985: Local radio show host Bob Harkins hears about The Secret Journal and asks me to his studio to discuss it. I suspect Barry was asked and, looking to avoid trouble, deferred to me as the fiction guy in the department. The book is on Harkin’s desk as we start, but looks untouched. Harkins asks me what it’s about. I tell him it’s about Mackenzie’s fears that the motives for his exploration are merely lust for money and power, and that Mackenzie thus represents the town’s history of destructive greed. Harkins listens for a while, lurches out of his chair, and says “I guess he thinks Prince George was a great town to grow up in.” This is more of an assertion than a question. I affirm that Brian definitely did think that. Harkins turns off the equipment and leaves the room. I find my way out of the studio. So far as I know, the interview was never aired.

1993: Local historian and geographer Kent Sedgwick invites Brian to the Mackenzie Bicentennial Events held in Prince George. He and Brian fly into Arctic Lake on the great divide to greet the brigade canoeists. In a subsequent conference at the college, put on by the university and the college, I introduce Brian, who gives the keynote address. Much later, in an Email 17 August 1999, Brian asks me if I have a copy of my introduction, which he is kind enough to say, is “way more interesting than what I said.” He also asks, “do you remember what I said. It’s in the archives at UNBC which of course hasn’t been catalogued so I can’t find out anything.” I tell him that I don’t remember what I said or what he said.

2004, 11 March: Pacific Western Brewery’s “Good News Story of the Week” in the Citizen newspaper is “Thumbs Up to Brian Fawcett for winning the $15,000 Pearson Writers Trust Award Non-Fiction Prize for his Book Virtual Clearcut.” The fact that Pacific Western was started by Ben Ginter, who fired Brian from a job driving a bulldozer because he stopped the machine to have a smoke, makes for some rich irony. And maybe Ginter would’ve thought Brian did do a good job as a writer, and would’ve liked the story about him.

Also in 2004: Professor Rob Budde at UNBC launches a “Literature of Northern British Columbia” course featuring Virtual Clearcut as well as works by other northerners like Sharon Thesen, Donna Kane, Ken Belford and Barry McKinnon. Whether Budde is still teaching this course or something like it is unknown to me, but it’s doubtful that McKinnon would now be included. Budde, the town’s first and best-known postcolonialist, famous for publishing a sanitized teaching anthology of Al Purdy’s poetry that excludes some of Purdy’s “misogynist” and “racist” poems, seems now to think that Barry is a poet who poses a similar threat to youth.

26 March 2005: Brian is inducted into the Arts Gallery of Honour, run by the local Arts Council and the City of Prince George. Barry presents this honour to Brian, who is sunning in the Caribbean at the time.

29 – 30 March 2005: UNBC hosts the Writing Way Up North Symposium, featuring Brian Fawcett, who has donated a large amount of his personal records and correspondence (1951 – 2006) to the Northern B.C. Archives at UNBC. Fawcett gives a public presentation on March 29 in the UNBC Angora, room 7 – 150. The announcement for this presentation says, it will be “a tongue-in-cheek look at what Prince George has taught me — a set of rules.” He proceeds to read The Northern BC Rules, with The Regulations for Snipe Hunting, published by David Mason.

Following this, Dr. Si Transken, a professor of Equity Studies and Social Work at UNBC, presents a paper about what she calls the “real writer.” This writer is “a white Anglo, middle-aged to mature male, slightly tortured by the vastness and burden of his incredible and rare talent. He is a drug abusing, alcohol abusing, women abusing emotionally volatile person. He wears tweed, and loves being at an academic podium. Real writers are intense, obsessed, lonely, and self-absorbed.”

Barry, Brian and I, all in tweed at the time, suspect that Dr. Transken must be talking about us.

March 2015: On the 100th anniversary of the incorporation of Prince George, Brian, on behalf of local lumber magnate George Killy, who played little league baseball with Brian in PG, presents 14 pictures by Regina artist David Thauberger to the Two Rivers Gallery. Killy, who sold his mill to become a major patron of the arts in Vancouver, has commissioned the pictures, and published them in a book with an introduction by Brian.

Well done! Went to high school with the twins…very interesting!

[…] readers at the airport. Over the next few years, I got to know a few of Barry’s literary friends, Brian Fawcett, Brett Enemark, John Pass, David Phillips, George Bowering, Ken Belford, Sid Marty, Cecil Giscombe, […]