Oxford Charles

I first saw Charles sitting on his backpack, snuggled between a bunch of Nepalese peasants in the back of an old, beat up, Indian-made truck. He looked out of place with his creamy white skin and in his sparkling white shirt, his leopard-skin silk scarf, his designer, button-down jeans and his brown felt fedora.

When we got to the end of the road, Charles got out of the truck carefully and then hauled out a cigarette holder, pushed a cigarette into it and lit up.

I wondered what this character was doing in the Nepalese mountains.

I was soon to find out. Charles ended up sharing a room with me and another girl and then accompanying us on a three-week hike around the Annapurna mastiff. It turned out that he was a dropout graduate student in mathematics from Oxford University and he was in Nepal to “sort things out.”

Charles was a bit of a hypochondriac. He carried sun cream, insect repellent, skin softener, two types of malaria tablets, antibiotics (for his stomach), topical disinfectants (for cuts and scratches), tibia for giardia, Tylenol for headaches, Diamox for altitude sickness and every type of bandage you could buy. He had bowel stoppers and starters, tiger balm for sore muscles and an inhalant in case he caught a cold.

His first aid kit was padded with a half dozen rolls of toilet paper. Except for the fact that he’d forgotten a razor and wouldn’t be able to buy one until we got out of the mountains and back to civilization, he was well prepared for his long hike to 17,000 feet.

Charles enjoyed the food on the hike, but, like the rest of us, he enjoyed even more talking about the food he enjoyed at home. While we all talked about hamburgers or waffles with butter and maple syrup, he would reminisce about flambés or cognac. Most of us had never tasted either. When I told everyone about the dehydrated bananas or spaghetti or split pea soup that I ate on long hikes in the Canadian wilderness, Charles talked about the roasted pheasant with orange sauce that he would enjoy after a walk in the English countryside.

We talked about other things too, in the evening after a long day’s hike. People would compare their record collections, which included everything from Motley Crue to Willy Nelson. Charles, not wanting to be left out, would talk about Mozart, Bizet or some other obscure (to us) musician of long ago.

When we talked about our various journeys around the world, Charles would talk about the first-class cruises that he went on with his parents. He also had very sophisticated political opinions in which he believed implicitly.

But the hike gradually silenced Charles. He was having difficulty keeping up to some of us. He had some of the milder symptoms of altitude sickness and was afraid. He had blistered hands from the harsh sun. At the base of the pass, he said nothing but stepped aside and took his Diamox. When, farther on up we stopped again so the stronger trekkers could take some weight off the weaker ones, Charles stopped and took some from me. At the summit, we had become a group of ten hiking together. We dropped our packs around the prayer flags and had a tablespoon of apple brandy that one of the fellows had carried up and was willing to share. Then we took the obligatory top-of-the-pass photo.

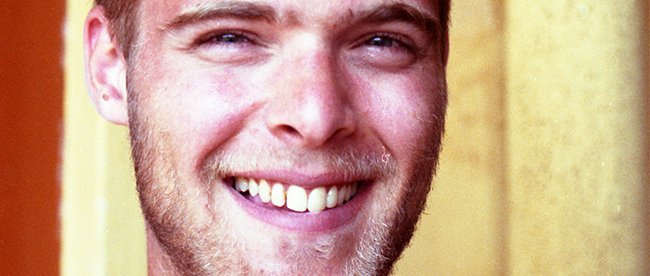

On our way down, I noticed Charles looked different. His white shirt was the regular sweat-grey colour like the rest of our clothes. His silk scarf was now a belt around his dirty jeans and his fedora was at the bottom of his pack. The skin that was visible around his two-week growth of beard was tanned and glowing. His teeth shone through when he smiled and his eyes sparkled. By this point Charles had given most of his medicine to others who had become sick while crossing the pass. He now used his cigarette holder to pass around the evening joint.

When the talk turned to travel and food, Charles still mentioned flambés, cognac and Mediterranean cruises but he also asked people about the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Beijing Express and the hike to Machu Picchu.

On my last night with Charles, we were in a rustic room that had an open ceiling with rafters holding sacks of wheat. We went to bed and Charles fell asleep instantly as did the other girl with us but I watched the rats running across the rafters, squeaking as they fought each other for any extra kernels of wheat that may have fallen out of the sacks.

“Charles,” I whispered. “If one of those rats falls on me I’ll catapult back to the pass.”

“Don’t worry. If one falls, I’ll grab it and throw it out the window.”

I don’t know what happened to Charles at 17,000 feet but obviously he had sorted some things out and was off to do some challenging things.

It was 25 years ago that I wrote the story about Charles for the Citizen. Charles had gone off to Russia after Nepal to learn Russian and we corresponded a few times before going our separate ways as is common with young travellers. Then, last week while scanning through the old photos, I saw one of Charles. I found him on Facebook and he remembered me so we re-connected.

Interesting that my predictions were correct. Two years after we hiked together he went back to school and started his PhD in Economics at MIT in Boston. He found a mate and moved to New York where he worked for JP Morgan. However there was a bit of a mix up in his visa so he returned to England where, sadly, he became very ill. But true to Charles’ form he totally recovered, moved back to the States, separated from his partner, and took up playing the piano. In the last two years he learned to play all of Bach’s preludes and fugues. Wow!

So now I wonder what his future will be. I am sure it will be exceptional and I hope to live long enough to get the next update.