Post Pogo

Michael Walzer’s piece in the February 28 Persuasion is a timely caution against “Woke” historical revisionism — against, to use one of Walzer’s examples, the idea that Thomas Jefferson was not a hero but a moral monster because he owned slaves and took one as a mistress. The revisionists tend to argue that, because he was a monster, his statues need to be removed from public places and the Declaration of Independence and Constitution need to be suspended or at least regarded as seriously compromised. The fact that Jefferson himself said they were seriously compromised, and predicted some of the future results of that when it came to slavery, is taken to be a sign of sheer hypocrisy.

A parallel example for us Canadians would be John A. MacDonald, who put Canada together but also wrote the Indian Act and built the residential schools. I’ll stick with Jefferson in order to better deal with Walzer’s argument, assuming that it will be easy for Canadians to extrapolate.

Walzer calls the statue-topplers the “new revisionists.” They, he says, “leave us nothing to admire in our past.” They make us long for George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and Abraham Lincoln as we once knew them, as heroes. More seriously, the revisionists erase the pride and confidence of Americans in their democracy and their liberal culture. Because the revisionists suggest no alternatives, nor even any improvements (an action that might make them complicit in the evil that their democracy has done), they spread a kind of political and cultural nihilism. Finally, they cause us to disrespect our ancestors. We act like we would never have allowed ourselves, as they did, to leave, or be transported out of, some European slum or third-world country to become citizens of a nation that stole its territory from indigenous people and built an economy partly based on slavery.

The moral reductionism of the revisionists infects everything. What Walzer calls “political contradiction,” wasn’t just a problem with slavers and segregationists. He points out that a lot of early abolitionists were ardent Protestants and therefore hated Catholics and were against Irish immigration. So how could racists be doing anything meaningful to end racism? He suggests that, if we carry on thinking like this, it becomes evident that all American politicians, and all citizens, past and present, are racists, and that nothing they ever did has any value. So never mind toppling the statues: bulldoze everything and evacuate the place.

Walzer continues, “What we should see in the contradictions I’ve described is not simple hypocrisy or self-regard but the common doubleness of political action, driven by private interest and public commitment.” Walzer wants us to add humility to our righteousness, to accept the good that heroic people have done and learn from their evil.

All well and good, but Walzer focuses overmuch on “them” — on our ancestors in this place. He’s still assuming that liberals like us, people engaged in battling racism, sexism, and discrimination against the fat, the handicapped and the ugly (euphemisms are likely required here), are on a higher moral plane than earlier liberals like Jefferson.

I think that this assumption indicates a kind of blindness — a kind that has well-meaning people pulling down statues of Jefferson and at the same time using cellphones containing rare metals mined by children in the Congo, wearing clothes manufactured by indentured workers in Bangladesh, and eating food produced by underpaid and abused immigrant workers from Mexico. What’s happened is not so much hypocrisy, self-interest or ignorance of the doubleness of political action, and more of an instinctive shift of focus.

We liberals tend to say about the doubleness of our own political activities, when it is drawn to our attention (usually by conservatives), something like this: “We have to go along with the ways things are done while working to solve the problems that are created by the ways things are done. That’s why I drove my car to this pipeline protest. That’s why I don’t turn my property over to the indigenous peoples who really own it.”

But that sort of argument would be, likely, Jefferson’s argument for keeping, and even for having children by, slaves, and for leaving slavery in the Constitution by avoiding any mention of it. He would argue about his slaves that, in the context of a slave state, he protected them, gave them social status, and freed some. He did what he could. He would argue that the Constitution was written for white men only because it otherwise would never have been written at all, and certainly never adopted.

Our blindness exists throughout history because we have to DO things to solve our problems and stay alive. Action, because we are not gods, because we exist in time, blinds us morally. Action requires compromise, accommodation, the simplification of motivation, the cutting of ideological corners, the forgetting of things.

It’s when we act, and not before, that the peculiar nature of our blindness reveals itself on any issue. It’s then that we have to move on to remove the flaws in what we’ve done, getting used to the fact that civic perfection is forever beyond us — probably because circumstances change quickly and human nature doesn’t change at all.

It takes time for us liberals to effect what we call “progressive” change. We have to drag conservatives along, and they’re pretty stubborn in their attachment to what is — an attachment that is strong even if they don’t like what is. They fought scientific change for a long time, until they figured out that, if they didn’t stay ahead scientifically, it would be hard to win wars.

Walzer’s illustration of the compromises that liberals have to make to drag conservatives along is the New York magazine Democratic Review (1837 – 1859). The editors were against capital punishment, for labour rights, tentatively for women’s rights, and silent on slavery. Walzer calls this a “gross contradiction,” saying, “On the most important issue of their time, they failed as champions of democratic equality.”

But white women and workers might not have regarded it as “the most important issue.”

The British Economist magazine, birthed by Whig journalists in 1843, in the aftermath of the Reform Movement, would’ve considered the issue of slavery not that important, because the British had abolished slavery some time before, and were moving on to other things. But, in a “mea culpa” for its history, published in its 11 July 2020 issue, the Economist admitted that it took a bizarre approach to abolition in America, arguing “that abolition would be more likely were the Confederacy to win America’s civil war.” Also, it supported European colonization, backing the Second Opium War, “the brutal suppression of the Indian mutiny,” and “the invasion of Mexico by France.” It wrote that North American indigenous peoples were “helpless . . . to restrain their own superstitions and their own passions.”

The Economist is probably at present the best, widest-read and most influential centrist purveyor of news and commentary in the English-speaking world, and that is probably because it has learned not to trust itself while it pumps out commentary — commentary that almost always includes recommendations for specific action.

Walzer’s correct about one thing. We need to decide who the heroes of the past are, learn from them, and put aside their shortcomings. We need to be proud of them and what they created, while we work to protect, improve and expand their creation. We need to avoid the nihilism of Black Lives Matter (“defund the police!”), of Me Too (“ban Woody Allen!”), and academic postcolonialism (“down with the West!”).

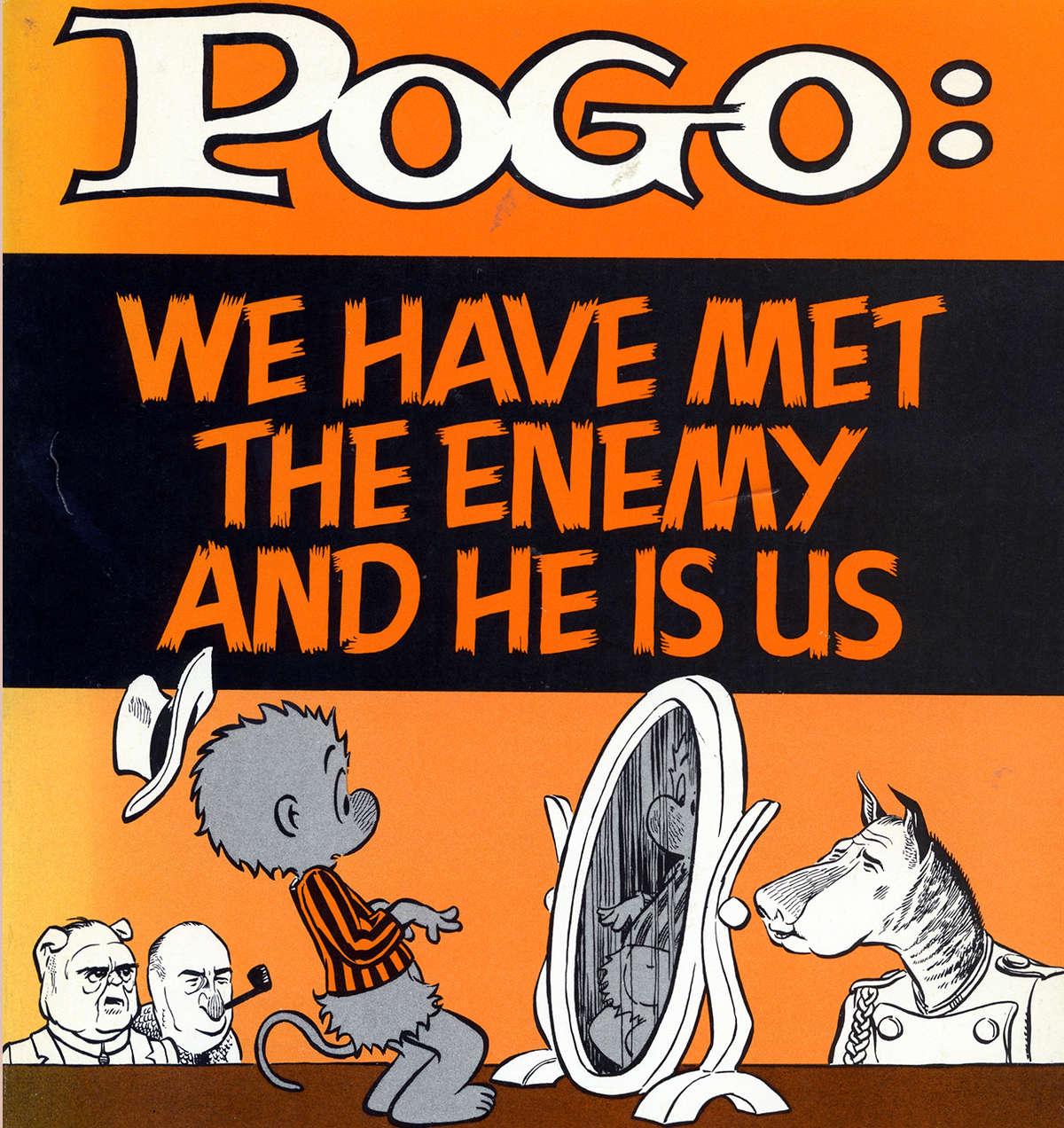

We need to acknowledge that, as the old Pogo cartoon put it, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”