POW Camp 132 Drawings

In the middle of October 2013, Viv and I received in the mail a file, sent by Bob Atkinson’s widow Karen Mackenzie. The file, Karen said, held drawings that Bob had told her, “were from some German prisoners of war in a camp near Medicine Hat.”

In the Autumn of 1971, Bob Atkinson, Paul Nedza and I, all employees of Medicine Hat College, started Repository Press. I left the college nine months later for a job in Prince George, and Bob followed a few years after that.

It was likely in those two years, 1972-3 to 1974-5, that Bob acquired the drawings; I don’t recall ever hearing about them. Likely he acquired them with a mind to publishing them, as he managed acquisitions for book publishing then — Alban Goulden’s In the Wilderness and Andy Suknaski’s Leaving as well as the massive Suffield Archaeological Project published under a separate imprint. I edited our little magazine Seven Persons Repository and Paul and his wife Avis managed artwork and the technical side of offset printing for both the press and the magazine.

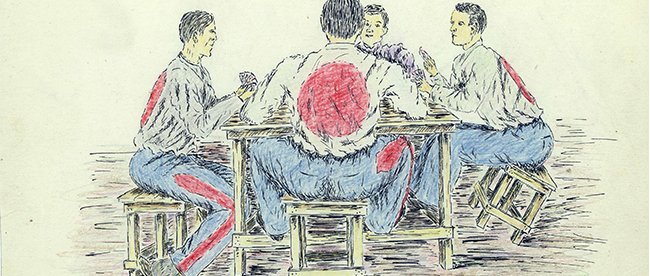

Bob’s file contains two distinguishable sets of pencil-crayon drawings, one a series of nine, fairly stylized (perhaps copied) “girlie” pictures, and the other a series of 13 camp drawings. Three of the camp pictures are of men, indoors playing cards. The men are wearing their prescribed uniforms of denim pants with a red stripe down the right leg and a large red circle at the back of the coat that looks, ominously, like a target.

There is one picture of the Nile river identified as “Cairo 12 Dec. 1941” that we include in the “camps” set because of its style, date and signature (see below). Both sets of sketches are done on heavy paper cut to assorted sizes, the smallest 18.5 x 24 cm and the largest 23 x 33 cm. The girlie pictures are all 18.5 x 24 and are fully colored; most of the “camp” pictures are larger and only partially coloured.

Six of the “camp” sketches are signed, including the one identified as “Cairo.” The name is hard to read, but seems to start with a V or maybe a K and be something like Vielber, Vielben or maybe even Keller. Two of the signed sketches say “Ozada” and three “Medicine Hat;” Ozada is presently a ghost town near Canmore in Alberta and Medicine Hat a small city in southern Alberta. The two Ozada sketches are dated 5 Nov. 1942. The three Medicine Hat sketches are dated “10. Oct. 1944,” “18. Febr. 1945, and “12 März 1945.” The dates are punctuated, abbreviated and spelled in the German style.

Planning for the Alberta camps, in Ozada, Lethbridge and Medicine Hat and built in that order, started in March, 1942, after 4,000 POW’s, members of Rommel’s Afrika Korps, were accepted by Canada. The Korps had come to Africa in March 1941, and, in the course of fighting, which lasted until February 1943 when Rommel was pulled out of Africa, some hundred thousand prisoners were taken and distributed around Britain’s empire. The first of these prisoners, our artist among them, went to Ozada, which started taking prisoners in May 1942. The bulk of these would have surrendered after the battle at Tobruk, November 1941, where some 36,000 of Rommel’s men were taken prisoner. The Cairo sketch is dated December 1941 — our artist was likely marched or transported to Cairo and then shipped out to Canada, probably by way of Britain. The Cairo picture, because it is on the same paper as the other sketches, was likely sketched and dated from memory, done in the camps and not in Cairo.

The history of the three Alberta camps is described by Robin Warren Stotz, in a Master’s thesis submitted to the History Department at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. As Stotz says, Ozada was never built up as a permanent camp. Starting in May 1942 it held at its peak 12,500 prisoners, all of whom were gone by December 1942 to Lethbridge. Medicine Hat didn’t open until February 1943.

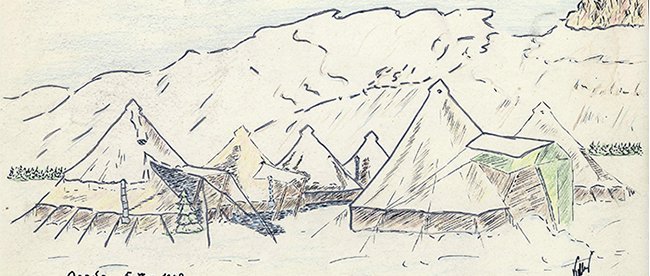

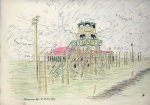

As the sketches show, while in Ozada, the prisoners were housed in army surplus tents that came from the US. Guard towers are visible in the distance. Stotz says that the camp had twenty of these towers and a few relatively permanent administrative buildings. In the more complete or colored-in of the sketches, the tents and buildings are covered by snow. There’s no knowing how early in the camp’s short life our artist arrived, but if he was in Cairo in December 1941 he probably came early, maybe even in the spring of 1942. He was obviously there near the end, during the first months of winter.

The camps at Medicine Hat and Lethbridge were the largest in Canada, both holding at their peak about 12,000 prisoners. The one at Medicine Hat, Camp 132, was the most notorious of all the camps in Canada, as the guards lost control over it, allowing it to be taken over by Nazi and S.S. POWs. Some, around 20%, of the early POWs, like those from Africa, were dedicated Nazis; later, especially after Normandy, the percentage of Nazis quickly declined. The situation at Medicine Hat worsened as the Nazis murdered two POWs, including one functioning as the camp doctor, Dr. Karl Lehmann, who was trying to stop the Nazi takeover by resisting it and bringing it to the attention of the Camp Commandants.

Tensions between the Nazi/S.S. group and the other prisoners — those who wanted church services, attended democracy lessons and/or were convinced that the war had been lost — continued right until the end of the war, though the balance of power shifted as the officials investigated the murders and moved confirmed Nazis elsewhere. Decisive too was the arrival of many new prisoners after Normandy. After the War, as the POWs were returning home, the RCMP concluded its investigation into the murders and five prisoners were hung.

There’s no indication of this struggle in the Medicine Hat sketches. It may be that our artist missed the worst of it, possibly because he stayed in Lethbridge for most of that time. The Nazis murdered their first victim in July 1943, and Dr. Lehmann was killed in September 1944. The first sketch of the Medicine Hat camp is October 1944. At the time the authorities were moving prisoners around to break up the Nazi domination in Medicine Hat. Our artist may have been brought in to replace a Nazi, presumably because he was known not to be one.

We wish we knew more about him. We hope by posting this and the sketches on our website we can attract more information. Meanwhile we are trying to find out his name and fix his history in the Alberta camps. Also, many of the POWs interred in Alberta returned after they were shipped out. Those with good records in the camps were welcomed. They had learned some English and been indoctrinated in democratic ideas in courses offered by, among others, Dr. Lehmann. Maybe our artist came back and has family in Canada.

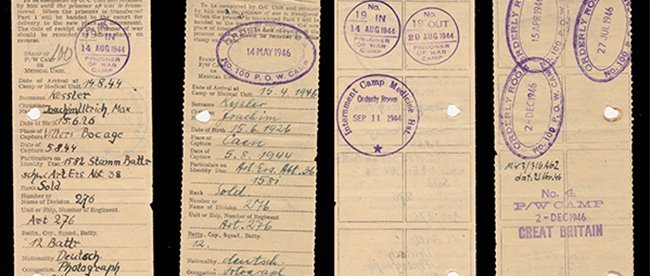

Jochim Kessler added the following information from Camp 132

During World War II, the Canadian Government housed over 34,000 German Prisoners of War in 25 camps across Canada. Camps for refugees were already in existence before the POWs arrived. There was such great urgency to find places for these people that in both cases the settlement happened before the terms of agreement had been signed with Great Britain.

The first “civilian internees” arrived in June 1940 while Britain and Canada were still negotiating. As the talks proceeded, POWs started arriving. But even this didn’t follow the rules. The first shipment included Jewish refugees. The Jews and die-hard Nazis were being shipped and, at first, settled together.

The largest camps, in Medicine Hat and Lethbridge, Alberta opened in the winter of 1943. Camp 132 in Medicine Hat covered 50 hectares of land and could hold 12,000 prisoners. Surrounding the camp were barbed wire fences and sentinel towers placed in strategic spots. Each of the 36 dorms housed 350 men who slept in double bunks. There was also a mess hall, education huts, workshops, storage barracks and kitchens, which were worked by the men. There was also a dental clinic, a hospital and a morgue.

Camp 132 held the high-ranking Nazi officers. This is where most of the Nazi propaganda took place, causing problems with those who had lost their devotion to Nazism or never had it in the first place.

The prisoners were generally treated well by their guards — most guards didn’t even have rifles, and were retired WW I soldiers who could understand and sympathize. The food was plentiful, the barracks warm and the men could purchase goods from a mail order catalogue. Some even managed to get jobs with local businesses such as Medalta Potteries or they worked as farm hands in the region.

One such prisoner was Joachim Kessler who became a close friend of the Freeman family and was so admired by the children, they called Kessler “uncle.” He remained in Canada after the war.

Artimus Freeman is one of the Freeman children who remembers Kessler with great affection. He provided the two photos and the travel documents he received from Joachim Kessler that are posted here.

There are two or three Master’s and PhD thesis written about the camps in Canada. These studies deal with government studies of the camps and the activities among the prisoners.

There are also two books, Behind Canadian Barbed Wire by David Carter (1980) and Escape from Canada by John Melady (1981). Both attempt to reveal what camp life was like.

Camp 132 was where the Medicine Hat Exhibition and Stampede grounds are located today. The camp closed in January 1946.

Examples of the drawing received by Bob Atkinson

Hello there, I have 2 watercolour sketches from the Medicine Hat P.O.W. Camp, where my grandfather was a guard, along with several other items he bought from prisoners. This includes a ‘ship in bottle’, similar to one in another website I just looked at. This article is the first I’ve seen with other sketches from the camp!

I have a painting by a POW given to my grandmother in Lethbridge Alberta from 1945.

It is a of a dancer and a conductor in an orchestra pit.

I’d love for you to see it and possibly identify the artist. It’s signed with initials only and a date.

Thank you

Hi Karen – sorry for the delay in answering. The paintings from 1945 POW camps are special and our collection is now in the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton. I have no idea who did the work but I am certain, if you contacted them, they would be eager to add your image with their collection. And keeping your grandmother’s name with the painting would be a nice rememberance. I always feel putting something like this into a museum saves them from the dumpster when the kids clean out the house. Good luck with your painting.