Silver King Basin in the Babine Mountains of BC

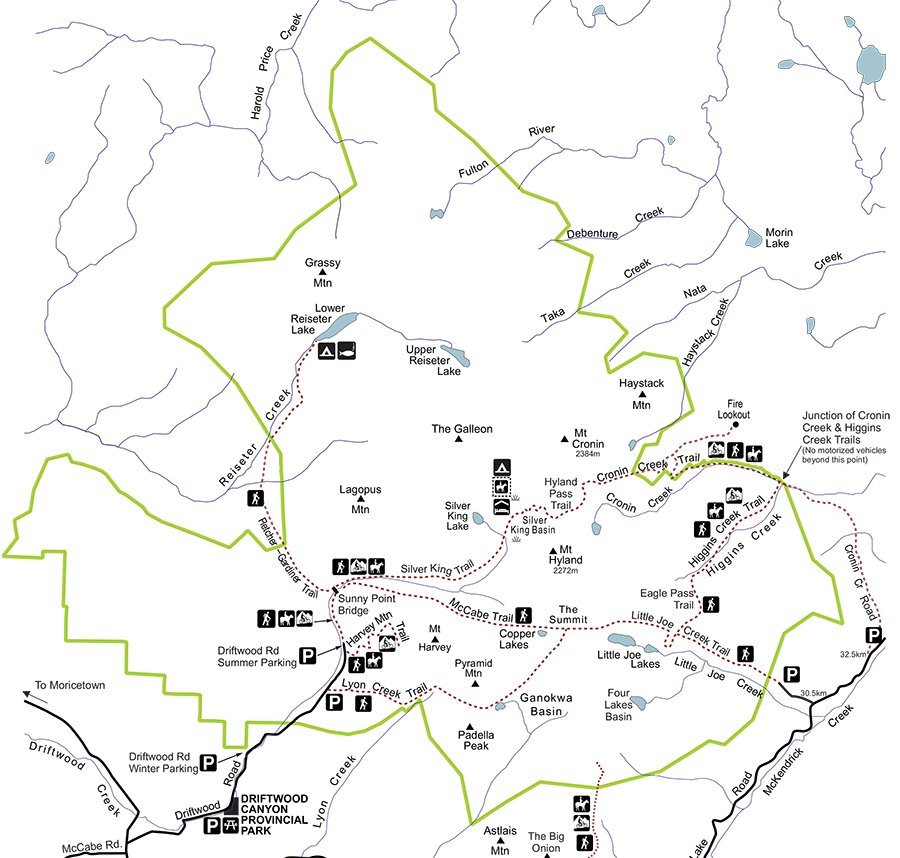

Silver King Basin! Just the name was a draw for me to explore Babine Provincial Park located north of Smithers, BC. I enticed four of my friends to join me in late July when valley snow would be gone and the alpine flowers would be prime. I showed them a park map with a four-day route that looked like a “cake walk.”

We took the Old Babine Lake Road, three kilometers east of the bridge at the entrance to the town of Smithers. Signs directed us to Driftwood Canyon Park, just ten kilometers in from Highway 16. We stopped there for a few minutes to look for 50-million year old aquatic plant fossils from the Eocene Period. The land was willed to BC Parks by Gordon Harvey (1913-1976) shortly after his death so those living in the area could always be thrilled by the discovery of a fossil. We searched the shale hill but found nothing.

The summer trailhead at Harvey Mountain was another five kilometers further on. There, we slung our loaded packs over our shoulders and started up the old mining road, shaded from the blazing sun by tall cedar and spruce trees.

The mineral claims in the area were first staked in 1903, the first topo map was compiled by 1906 and prospectors were going up the same trail as we were on, heading to Silver King Basin, with gold in mind by 1907. These early explorers also built the first cabin in the basin just above the present cabin’s location. By 1915 miners were working close to 50 claims in the area.

We enjoyed the solid rock road that eased upwards about 150 feet every kilometer all the way to the cabin. The road crossed numerous streams, some bridged and the rest running through culverts. A few strong cyclists passed us as did some younger and faster hikers.

Four hours later we came across the Joe L’Orsa cabin, named after the man who, from 1973 until his death in 1997, successfully campaigned government to make all land in the area above 1300 meters into recreational property. This park received full park status in 1998. In his will, L’Orsa left money to build and help maintain this cabin.

Just beyond the log building is a campsite and children’s play park beyond. We dumped our packs on the porch and entered into a central room with a heavy cast iron stove that was fed with wood from the shed out back. The room is framed by metal-covered counters on three sides and has a number of picnic tables for comfy eating. Off the main room are two bedrooms complete with six bunk beds each. A stairway leads to three more rooms, two of which are meant for families. In total the cabin holds 20 people comfortably but in a pinch, it could probably jam in double that many.

We occupied the campground, Sandy poured the wine she had hauled up (bless her) and watched the cabin fill. Over the years we have discovered that cabins are to be avoided if possible. Snores abound. People come and go all night long to visit the loo and usually, kids get up really early.

After a quiet sleep and a bowl of porridge, we headed to Highland Pass farther up the valley, checking out the remains of mining era: ore cars and their tracks, adits cut into the hill and buckets, pipes and pick axes rusting on the rock. At the pass we could see mountains, some still snow covered, some golden, others grey and still others that were streaked and interwoven with all colours. We could also see Silver King Lake glistening in the sun on the mountain opposite the cabin. There was also a lake on the pass and mounds of rocks from where we took numerous photos before heading down the Cronin Trail to a cluster of tiny lakes and a boulder field beyond.

There we played for the rest of the day, jumping from boulder to boulder and circumnavigating tiny lakes. We noted an abundance of moose and grizzly tracks, days old, and watched a fox trotting across the alpine looking like he had a purpose.

The following morning we sauntered back down Hyland Pass, past the cabin and over to the McCabe Trail located just a couple of kilometers above the car park. The trail was an old wagon road that skirts the backside of Harvey Mountain. This new trail, an easy hike after climbing the first hill, led to Little Joe Lakes about ten kilometers from trailhead.

The McCabe Trail is clear and well marked, the campsites numerous and the mountains breath-taking. We dumped our packs at the Mineral Lakes about five kilometers in and set up tents before continuing up valley. Unhampered by packs, we strolled along to the music of marmots whistling our arrival. Linda spotted a herd of goats perched on the rocks on the far side of the valley and cursed because she couldn’t get close enough for a good photo. According to historical documents at the museum, goats by the hundreds dominated the landscape but with so much human traffic, they have moved farther into the Babines.

We stopped for lunch above Little Joe Lakes and then sadly, headed back to our campsite near the Mineral Lakes. The following morning, it was an easy out, back down the McCabe Trail. On passing the juncture of the Lyon Creek Trail that leads to trailhead, we contemplated taking it for a change of scene. But it was longer and steeper than the McCabe so we decided to leave it for the next visit.

This park is kid-friendly yet has numerous challenges for those wanting more wilderness hiking. The main trails welcome cyclists and dogs although dogs are not permitted in the cabin.

For more information and a good map go to http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/bcparks/explore/parkpgs/babine_mtn/

For the most complete historical records, visit the Bulkley Valley Museum in Smithers. In their archives, you will find the R Lynn Shervill Collections that include hand written notes, newspaper clippings, mining reports, photographs and research correspondence.

For exciting stories of the explorers, old and new, explore Sheila Peter’s blog at https://sheilapeters.com/blog/.

For a complete report on the geology of the park go to http://www.empr.gov.bc.ca/Mining/Geoscience/PublicationsCatalogue/Papers/Documents/Paper1992-05-TheBabineMtnRecreationArea.pdf .