ThimbleBerry Review Spring 2021

The latest (Spring 2021) issue of ThimbleBerry, Art and Culture in Northern B.C., provides a cross-section of literary accomplishment, artistic creation, and aesthetic thinking in the region. For the magazine’s editors, Rob Budde and Kara-lee MacDonald, these accomplishments are vital to “societal well-being.” Their introductory “Letter from the Editors,” which starts in first-person plural but shifts to singular (the “I” being Budde, it seems), describes the difficulties generated by the Covid epidemic, along with other longer-running social difficulties. Budde asks, “how does a well-designed, pretty arts magazine affect a homeless person sleeping in a cardboard box on 3rd Avenue in Prince George?” His answer is that “art and culture expressions of power dynamics and societal relationships galvanizes a healthy ecosystem of needs and resources. By these measures, Thimbleberry Magazine has a role in the overall quality of life of all of Northern BC.”

Budde is a creative-writing professor, with that humanistic idea of the high place of literature in the scheme of things — an idea that is used to justify his trade, which is the teaching of literacy using literature as a model and subject matter. English and creative writing professors believe that using literature in this way provides safe (non-political) topics for composition, and also applies a patina of culture and morality onto the young. In this way art and literature add, as Budde says, to the quality of life.

Overall, Thimbleberry proves his point, starting immediately with a three-page poem by Erin Arding Stewart of White Rock. “The interaction of objects” deals in part with writing while raising children, and conveys through its repetitious phrasing and iconoclastic wit the hallucinatory monotony of non-stop attention to a child’s needs:

the pen fits in many places:

cylindrical containers and vent slates

through baby gates & bass amp grills

in cups,

behind coverings &

many undiscovered places . . . .

if you lay really still

the baby won’t wake

if you stay awake

sleep is that much closer

if you lay really still

the doctor will give you the sleeping pill . . . .

sometimes in November

there is semester burnout

sometimes job burnout, sometimes stove burnout

& there is no way to get more hot water into the

birthing tub . . . .”

Stewart won the inaugural Khasdzoon Yusk’ut (Cranbrook Hill) award for Most Promising Northern B.C. Writer [all contributors, even if they are now living in the south, have some connection with northern BC]. Judging by this poem, she richly deserves the award.

The next pages are devoted to a special section: “Ken Belford/In Memoriam.” Readers of earlier Thimbleberries will know that Belford is a sort of father-figure for both the editors and some of the regular contributors. He is a major poet, prominent in many anthologies including West Coast Seen (1969), Al Purdy’s Storm Warning (1971) and Margaret Atwood’s Oxford Book of Canadian Verse in English (1982). He lived in Prince George in the later years of his life, and published his later books through a local press, Caitlin. He died on 19 February 2020.

Budde’s tribute is in two parts, prose and poetry. In prose, he recalls that he first contacted Belford with a question about Steelhead Trout:

So I emailed him and soon received a reply in the form of a 3-page love letter to Steelhead Trout . . . I got a detailed description of the personality, family structure, and movements of the fish. He wrote about how the returning Steelhead recognized him, as they looked up from a pool that they returned to year after year. This careful attention and genuine love for the life of all creatures is what I would want you to know most about the Ken Belford I know. The image of him quietly standing by a river eddy, greeting the Steelhead individual and families, is something I will carry with me forever.

Budde recalls Belford’s knowledge of the land was “a blend of book knowledge, lived knowledge and traditional Indigenous knowledge, and came to be in stark contrast to the representation of ‘nature’ in Canadian lyric poetry.” He adds that Belford had three features: “one, a sense of the value of careful and considered negotiation; two, a wary eye to the machinations of affluent white men and, three, a deepening of his respect for Indigenous ways of being and knowing (TEKW).” [TEKW” means “Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Wisdom.”]

Budde concludes that Belford’s poetry “asserted an outside, an other, in two ways: a cultural distance gained from 30 years as a back-country guide trained by Gitxsan hereditary chiefs (foremost being Walter Blackwater), and in terms of gender expression, openly resisting the sexist ‘paternal’ and misogynist ‘boy poetry gangs.’ It was an ethics we shared as close friends and structured our stand in Prince George/Lheidli Tenneh Territory “against the status quo.”

The second part of Budde’s tribute, a poem entitled “On Paths and White Men, for Ken,” presumably objectifies some of the above views of Belford and his poetry:

young men . . .

shoving their way into the scene

as if it was a scene

and ‘daring’ poetry is stuffed in their

pockets to spend on booze

and groom women to spout

violence when the ward causes trouble

while the Internet boys shout “irony, irony”

and put out fires of difference . . . .”

All of this, both the prose and the poetry, leaves a bad taste in my mouth. It pulls the race card, dividing people into “White” (bad) and “Indigenous” (good), putting Belford solidly on the Indigenous side. It seems as if Budde is using this schema to score points against vaguely defined enemies, like “the status quo,’ “affluent white men,” “young men,” “Internet boys” and Canadian nature poets. But isn’t Belford white, from the south, his poetry representative of modernist forms, among which is the “nature” poem using the “pathetic fallacy” trope (Belford knows that the fish recognize him). And isn’t Budde white, with therefore a questionable claim to the authority to identify Belford’s indigenous qualities? Isn’t he also from the south (USA), affluent (as a professor), and active on the Internet?

Josh Massey’s poem, on the other hand, “In Memory of Ken Belford,” is clear and thoughtful, with a powerful evocation of Auden’s tribute to Yeats:

When the big voices depart

they do so on the big stage

ply currents of history

like Cohen exiting in Fall 2016 . . . .

So Ken Belford departed us

with January temperatures bobbing

lower than when Yeats vanished

to the ring of piercing complexities

nonetheless escaped before the big one . . . .

He admired fish personalities

spoke of fish families, special life, complex life

dangerous in a special fucking world life

that ought to be treated real special

if humans have any decency left in the tank . . . .

Massey powerfully expresses the sense of the permanence of loss:

When he and his wife did the work of a crew of nine

Building a lodge in Blackwater, breaking trail away

From the glaring saw bones of dead ideals

Passing through those green mountain pages

still, or has. And his leaving leaves a void in the land . . . .

The poem concludes by expressing the remote possibility of hope:

He’d be the first to say

death lacks fixity, like words tend to,

so his absence both purrs and roars

gales against the rocks of the mountainside

the moving of warm mugs along our hands

Si Transken, who became Belford’s second wife on April 21, 2007, is a University of Northern B.C. sociology instructor, and a social activist in the community. The title of her tribute is “Dark Green Ink,” and her focus on and attitude to her husband’s writing implements makes for a poignant tribute:

He’d used

a particular righteous pencil for decades

he wrote on particular pocket pads in the forest.

Publishers celebrated his tender,

humble, bush-boy persona.

I am writing this on his keyboard, his computer, his screen

with his printer as my next step. Alonely. . . .

Curious & kind he sits waiting and writing our stories.

The word “alonely” stopped me, until I realized it was an evocative use of “a” as a prefix, meaning “in the state of being.” It could also indicate that Si is neither lonely nor not-lonely (as in “amoral”) in the sense that she is, even though Ken is dead, engaged with him in their writing.

A column by Andrew Kurjata, award-winning radio producer and journalist, talks about the geographical and cultural advantages and disadvantages of living in Prince George:

It’s a place where you can, when the weather’s right, take a bus to go cross-country skiing in the woods or even go skating on a frozen pond over your lunch break. And being the biggest city for hundreds of kilometres in all directions, it punches above its weight in terms of services, from medical to educational to entertainment.

On the other hand, Prince George may not always be completely welcoming to some cultural or religious minorities:

As I was writing this column, I saw a post from a woman talking about how she had made the difficult decision to pass up a career opportunity in part because the employer told her, directly, that as a visibly Muslim woman, she may face racism and threats. That’s not something I’d have to think about, no matter where I move in this country. And yes, bigger cities are not exempt from these issues . . . .

Noting he is the moderator of an online forum about the city, Kurjata says that the questions he is asked sometimes centre on the sense of community here:

There have been a lot of questions about whether there are Queer-friendly hairdressers or how the locals feel about someone wearing a hijab. We live in a world where, more and more, people can choose to live wherever they want. Why would they choose to be somewhere they might feel unsafe, without support? In considering a move here, they want to know whether they will feel welcome. Not just tolerated: welcome. It’s up to us to decide how we’ll answer.

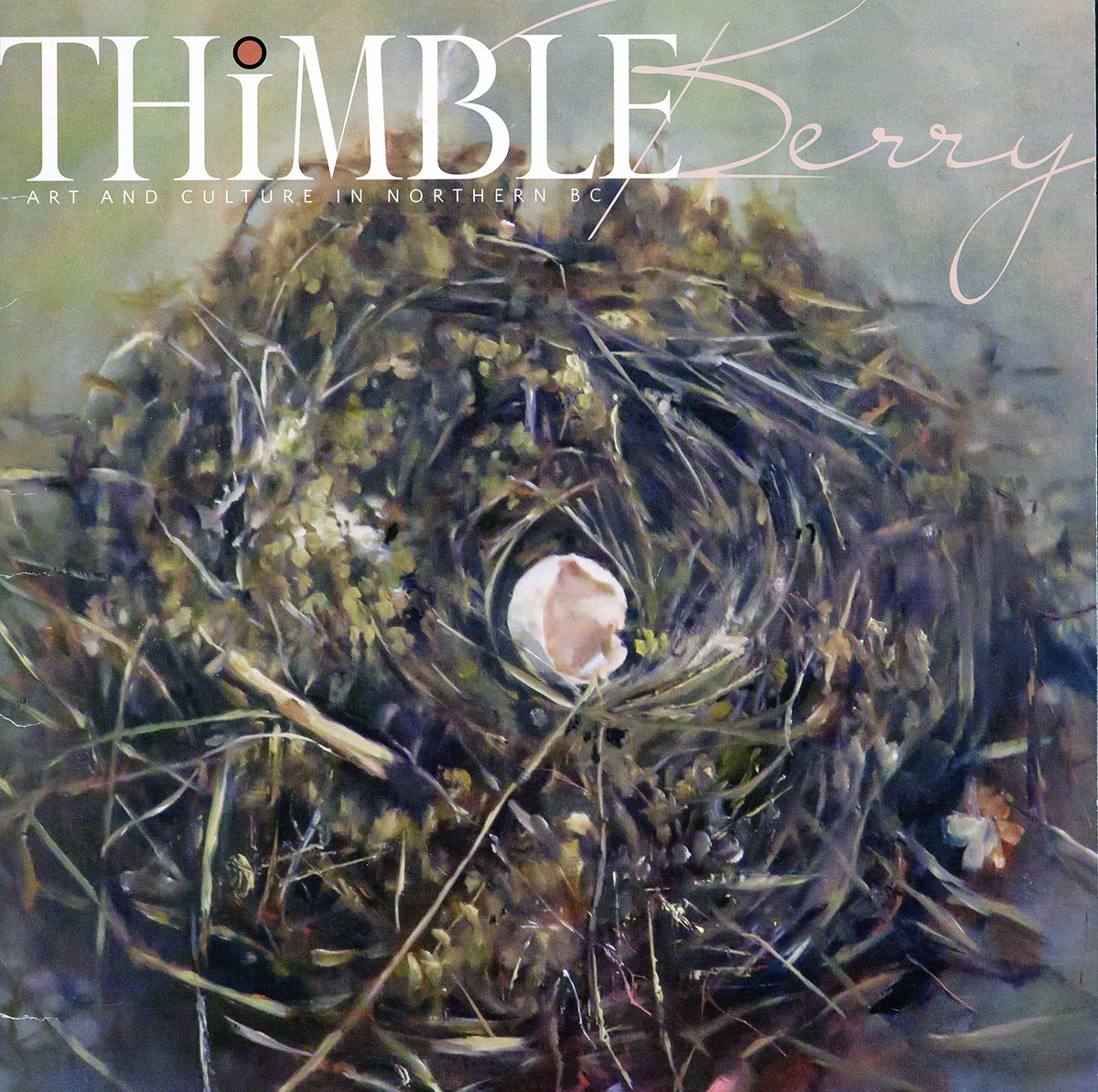

One of the two attractive art features in the magazine, “On Painting Nests,” focuses on the work (represented on the front cover) of Corey Hardeman, a Prince George resident who is trained in both architectural drafting and classical drawing. About nests, she says:

I ask people never to remove a nest that’s in use or in any way functional. Birds do return to their nests, and even when they don’t other birds and animals will make use of an abandoned nest . . . . I love that each one shows the character of the bird who made it . . . . I think also about how a nest is not a home . . . . It’s not a place to live. Birds don’t sleep in their nests unless they’re sitting on eggs or young. They’re built for one thing, and for one thing only, and that is the rearing of babies, and once those babies are fledged, they are homeless, or at home everywhere, depending on how you think of it. . . . . I suppose during the pandemic they seem a bit more urgent to me, or a bit more universal. Little husks of old lives, little reminders of the trees now untreed. They both comfort me and unsettle me.

Naomi Kavka, songwriter and musician, writes about the work of a noted local performer in a column titled “Patchwork and the Music of Brock Paciejewski.” Paciejewski grew up going to metal shows, and Kavka writes:

The recent torrent of folk musicians in the region informed his song writing, as he is a regular show goer as well as performer. However, he still feels the influence of the heavier music. . . . His songs are characterized by his calm and smooth voice, bright and reverberant guitar tone, clever lyrics, and chord progressions that on the surface seem obvious yet at the same time would make most songwriters ask themselves why they hadn’t thought of it.

Paciejewski, Kavka says, writes about personal topics like relationships and breakups, but he combines them with geographical references. About this, Kavka writes: “I cannot always tell if he’s writing the song to a person or to the land.” Finally, Kavka considers the matter that Budde brings up in his editorial, the effect of the epidemic on the artist:

Covid-19 greatly reduced the number of opportunities for Paciejewski to perform. Before Covid he could be one of the regular performers at the Legion, Trench and UNBC. Now it’s not very clear where he and other musicians will be able to perform once all Covid restrictions are lifted: The uncertain future of performance venues is certainly on many musicians’ minds across Canada, with many staple venues such local Legion branches facing potential closure.

Sari Dale is from Kelowna. Her creative non-fiction has appeared in The Fiddlehead and her poetry in Poetry is Dead, Room, CV2, Event, Grain, Arc and The Malahat Review. The first poem is “Gemini Moon, for Ash”:

. . . You said we’d live

in a cottage, like onscreen.

You with your lover, me with

my hounds. I’d be wolfish

wasted, wine spiked with

belladonna, deadly nightshade.

We’d brew lavender tonics

for our insomnia, sleep in

separate rooms till every-

one else leaves us. . . .

“Motion Sickness.” the second poem, has surrealistic elements:

She doesn’t

Understand how her

parents live loudly

without music. The

child hurts them in her

quiet way. Like birds

against a window, she

watches them screw

their heads back on.

The soullessness of some subdivisions figures in “Construction,” the last of Dale’s poems:

It is a river. It is warm.

Dreaming, they drive trucks

into stardust. This is a

house with God’s ceiling,

the insulation wrapped in

plastic. Just another

neighbourhood to forget

the name of. There are

words and places, but the

child is above language.

In his autobiographical essay, “Last Fall,” Adebayo Coker, who moved to Prince George from Lagos in 2016, describes the impact of his first winter in the area’s cold climate: “The Air Quality Report comes with a warning: Stay indoors, and keep warm if you must go out. I was missing the tropics already. The worst colds in Nigeria are never in the negatives. I am used to just two seasons; the dry season and the wet season.”

Stories and sayings from his African past sustain him through some of the difficulties of adapting to the climate. He experiences major injuries from a fall on “deadly serious ice, hidden between freshly fallen white snowflakes,” and ends up in hospital for days. At the end of the story, an MRI report turns out to be positive:

I gave [Dr. Burgess] a firm handshake with my left hand, though the pain was so biting, but pretended it was nothing, and before he could say anything more, I started walking toward the exit.

I’m an African boy. “a fowl would not die from a leg injury.”

In his poem, “Big,” Jordan Tucker of 100 Mile House mixes the details of astronomical distances and the myths of science fiction and interplanetary travel with the realities of flying to meetings in distant places with plastic environments:

We providers of interplanetary connectivity

are the real space cowboys. Beat-up ships soar

rusty miles for shit pay to provide this casual

right–communication across distances.

They say I am to return in fourteen 24 hour cycles,

back on Earth in day suits and brightly coloured dress shoes,

smile in unison as they relay my orders, faces slack

as they address the next ship, the next set of cameras. . . .

Each night there is a motivational speaker

dripping personal tragedy in the spotlight

of the cafeteria. I miss the man in Hawaiian shirts

Who plays a saxophone outside the hardware store.

I give him a toonie and we nod to one another

and that is the extent of our relationship, has been for years . . . .

Of our safe return I have no doubt. Titanic and Boeing prepared us for

this.

But who will I be when I get back? I am empty to bursting.

All of my journeys have been a painstaking return home.

I hope it is where I left it.

In “Shifting Culture: How Haida Gwaii has Adjusted to COVID-19,” Robert Williams, a councillor with the Skidegate Band Council, outlines the measures the Haida Nation implemented to protect its people, including declaring its own state of emergency. The reason for the Band’s deep apprehension was the historical memory of smallpox:

Reading and listening to the news media about how easily and quickly the coronavirus is spread brought ancestral horrors to the forefront, a sort of rememoration. At the time, the Haida Nation went from ‘an estimated population of 20,000 prior to 1770 to less than 600 by the end of the 19th century.’ The end result of the smallpox epidemic was the devastation of a culture, the loss of oral histories and language; and the fragmenting of families. Kii’iljuus, Barb Wilson, likened smallpox to “a fire burning a library of 30,000 books.” Indeed, the image of a massive library burning to the ground—its books containing the history of a people — is powerful and resonates with us today. . . .

Williams explains the governing structure of the Haida, which allowed the Village Councils to keep their state of emergency in place even when B.C. suspended its:

“In essence, the Federal and Provincial governments have provided us with a key opportunity to develop our own solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Those solutions include giving priority to Elders and engaging in physical distancing as opposed to social distancing. The latter can be destructive to mental health and the exchange of knowledge:

Advice to the people had the theme of “Do stay physically apart . . . Don’t become socially isolated . . . . Digital technology has allowed us to transcend the total isolation we’d otherwise feel if we had to keep our circle of friends limited to those in our immediate household. Social media, ZOOM, Face Time and similar apps have allowed us to connect with friends; they’ve allowed us to continue working; and, importantly, they’ve enabled our Elders to continue teaching the language and sharing their stories so that future generations can learn and benefit from their depths of wisdom.”

Sylvia Simons grew up in Prince George, but now teaches English as a Second Language at Langara College in Vancouver. Her poems are published in EVENT, Geist, Room, Best Canadian Poetry 2016, The Sustenance Anthology, CV2, Prairie Fire, and Arc.

The first of the two poems, “Shamrock Road,” reflects a gritty reality — the contrast between romance and the domestic life that follows:

The week her dog was in heat

she tied it so the hollow chrome

of a table leg . . . .

The clanging chain

woke the man in the bedroom —

the same man

from the wedding snapshot

laughing with a glass of bubbly.

His bride forever tucking a daisy

behind his ear.

Door swung wide, he squinted

into daylight. Sleep

still pressed to his sweaty head.

he seethed at us

through dirty teeth. His face

was grey. The same shade

as a pillowcase

washed too long in hard water.

“creek” is the second of her poems. It focuses on some of the realities and pleasures of actually existing in Nature:

you scramble down the bank

to sit on the twisted lip

of a culvert

canada fitness badge

stitched in silver

on your arm

water the colour of

pilsners muscling

under noranda road

Greg Lainsbury, a regular contributor, formerly from the Peace Country, writes a comic description of holding literary events in the north. It’s called “The Last Good Time/Outpost North/Fort St. John,” and is accompanied by detailed scholarly allusions and notations. The comedy lies in the discrepancies between two worlds. The first is the world of “the patch,”or Fort St. John, where Lainsbury teaches “at the local waste-disposal facility.” (He is described — has described himself — in the List of Contributors as being about to retire from his position as “Commissioner of Sewers” [thus the “last” good time]. Some of his students, he says, “require a complete public-vocabulary overhaul” before graduating and moving off the patch.

The second thing is the world some of these students, with great success, actually move on to, mentally and physically, with Lainsbury’s well-meaning but clumsy assistance — a world of truth (here represented by Plato) that can be accessed through thought and study: “without truth, beauty and love weren’t viable.”

These two worlds are manifest in the narrator himself. On the one hand, he plays the role of an ineffectual organizer and a person who “half the audience at the reading would cross the street to avoid.” On the other hand, he is a purveyor of scholarly wisdom and bearer of the torch of poetry through the heart of darkness.

The story starts with a photograph of participants at a poetry reading in a bookstore-headshop. Lainsbury has put on this reading as a tribute to the “Post North” instructors from Prince George who have hosted him in the past. Lainsbury refers to the necessity of refreshing his memory of the details of episodes “of my ongoing meta-literary history of northern B.C.,” and describes the steps required to properly accommodate literary guests, such as putting them up in rooms at a good hotel:

I was able to get two complimentary rooms from the Northern Grand for my PG guests, thanks to the manager, a very lovely and gracious lady whose name escapes me. . . . Graham [Pearce] travelled up with his wife Vicki and Matt Partyka. I’m not sure now if Tyler Crick and Laine Bourassa had come up from PG or Dawson Creek, which is where I think people from Demmit [Alberta] say they’re from when talking to outsiders.

He determines, on checking the photograph, that fewer people attended the reading than he recalled, although more were in attendance than could be captured in the frame of the photograph. This leads to the observation that “a distressingly high percentage of them are there because of the influence of more prosocial members of the Fort St. John Poetics Research Group, whom I’d yet to boot out for Ideological Impurity and Crimes Against Poetry.”

Lainsbury is an (I believe he’d like this designation) insanely funny man. I have a friend who would be eager to publish his “metahistory,” should a publisher friendly to irony and satire be hard to find, which is likely these days. A footnote seems to indicate that the satire has the working title of “The Mysterious Arrival and Untimely Demise of Henry.” I assume Henry is Lainsbury, his arrival is his acquiring of a job in the oil patch, and his untimely demise is his retirement.

Derrick Denholm’s contribution is a work of short fiction, “No Problemo.” According to the bio in the magazine, he writes about the problems of industrialization and globalization and their effects on the human psyche and wilderness. His books include Dead Salmon Dialectics (poetry) and Ground-Truthing: Reimagining the Indigenous Rainforests of BC’s North Coast. Both books are described as “ecocritical theory.”

Denholm’s story is Faulkneresque in its mood and sentence structure:

Straightening out our mental and material infrastructure, we trick-or-treated our way over the sidewalks of duff, fermentation, and litter layers of dead needles and branches between the last true firs leaning swamp-wise and the woodpecker-scoured monoliths of spruce that arched above a blue being dwindled down into black by dark matter. Filling our bags with whatever treasure we could find, we plucked our way here and there over the moss between lichen-speckled boulders shrugged off long ago by retreating glaciers.

Adam Katz’s poem, “Sample Delusions [for Ted Byrne],” reflects back on the art form itself. Its first stanza is in prose form, like a short essay:

I have tremendous respect for the poets who can write transrational lyric while awake (maybe that’s oversimplifying), because it’s so easy, when we think that this is the kind of writing we are doing, to just reinforce structures that operate by co-opting the tropes of transrationality, but, in my own waking poetry practice, I don’t know if I’m trying to resist anything there or not, but if I am I want it to be partly from a place of reason.

The portion in poetic form borders on surrealistic (note the changing sex of the dog in the final stanza):

how low can you go

without having to

touch the subtitles….

stomp down

don’t stomp down

if your weapon

is this morning

actual fantasy or horror

there a dog in there

keeping himself normal

does she have a deep dark bark

she’s about ageless

get him out of your dad’s car

This issue of ThimbleBerry concludes with an excellent art feature by George Harris, Curator and Artistic Director of Two Rivers Gallery, showing and describing the work of Twyla Exner and its focus on the hypertrophy of computer products and communications technology. Harris says,

In the midst of the pandemic, we are, by now far more familiar than we would like to be with the introduction of an unwanted infection gaining a foothold and affecting our lives. Prince George-based Twyla Exner’s work is interesting to consider in this context. Her work conflates tech with organisms born of the imagination and let loose in the world.

Accompanying Harris’s essay are photographs of Exner’s exhibits that depict telephone wire covered by woven yarn. Others show a group of computer parts climbing walls like large, potentially poisonous spiders. Two of the pieces are “Bacteria” (2008) and “Inhabit”(2012), both showing unfamiliar life forms adapting to their surroundings.

I was deeply affected by Exner’s art and Harris’s essay. Too often it seems our society thinks anyone who is concerned about the overgrowth of computer technology into every aspect of life is a buffoon or a geriatric Luddite. It is good to know there are some artists who see the danger, too.

Copies of ThimbleBerry sell for $12 and are available at Books and Company

and other locations in Prince George.