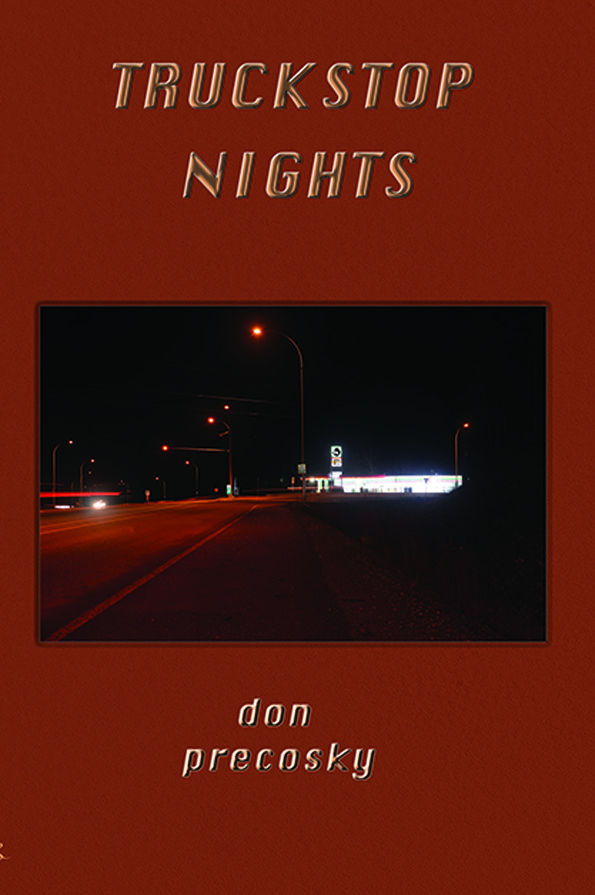

Truckstop Nights, Review

Don Precosky’s memoir, published by Repository Press, Prince George in 2016 is about how he put himself through university working exhausting all night shifts at a truck stop on the Trans-Canada Highway near the current Thunder Bay is painful to read. However, this is not a criticism, but a tribute to how well the book is written, and how accurately it describes the physical and psychological impacts of working too many hours.

The book recognizes the sacrifices of truckers, loggers and everyone associated with transportation in the North, and eventually rises to the heroic. It celebrates the truckers’ struggles, as if they were Greek soldiers trapped in struggle on the plains of Ilium before the unassailable gates of Troy. Precosky places the Trans-Canada Highway, an extraordinary achievement in the late 1950s and early 1960s, on the same level as the wine-dark sea of the Homeric epics.

In the early 1970s, Precosky was required to work from 1 p.m. to 7 a.m. three nights a week while attending regular classes during the fall and spring, and those same hours seven nights a week during the summer. It was a struggle for him to stay awake during lectures because he often had to go directly from his job at the truck stop to class.

It was also very difficult staying awake through the early morning hours while working an all-night shift:

“An all-night shift has a definite shape. It is like a capital V. You start and end high. In the middle is a big low. It’s all biological, quite beyond my control or responsibility. It doesn’t matter how well rested I am or how busy, my mood sinks, sinks, sinks, and reaches its nadir at about 3 a.m. It’s dark, the air is cold, there’s nobody to talk to. I’ve scraped bugs off windshields, scrubbed the toilets, checked oil on 50 cars: — now I’m beat and dirty and cranky. I’m sitting in my office fighting off sleep. The all night DJ seems to have gone off somewhere and the Lenny Dee album he left on the turntable drones on endlessly

“But then something slowly dawns on me. There’s light in the east (God, I know it’s a horrible cliche, but it’s true). Slowly the horizon brightens, and so do I. Birds start to twitter. It’s bright enough to turn the neon lights off, and my ears are spared that almost subliminal hum. The air changes . . . .”

Precosky finds truck drivers to be unpleasant and inexcusably small-minded at first.

“Truck drivers are among the most miserable, intolerant, loudmouthed, and cowardly people it could ever be your misfortune to meet. They sit high up in their cabs, looking down at the countryside and the people in it. . . . ”

The atmosphere in and around the truck stop is one of bugs, dirt, petty corruption, and taunting reinforcement of a vindictive work ethic. Reading and contemplation of the literary arts are most strongly discouraged.

Yet Precosky sees that the truckers lead grinding, soul-destroying lives. They have little or no time for home and family life, and family members and friends have little understanding of their situation.

“Think of the drivers. Think of the poor drivers. In the rain, in the sleet, in the baking sun, in the fog. Driving, Driving. Headlights tunnel through the pre-Cambrian night, boring a path between the rows of evergreens . . . .”

One is reminded of Walt Whitman:

“Think of the drivers, the poor drivers. Strangers at home, leaving the wife and kids alone. Crawling into bed to sleep all day to be rested for the next run. Spending Christmas Eve in the cabover in a parking lot in Nipigon. . . .

“Think of the drivers, the poor drivers. Time and space for them are to be crossed. Impediments. Not for him the scenic lookout. Not for him the long weekend. Drop the trailer at the terminal. Sleep four hours in the cab. Take another trailer back to where it came from. He needs no home, no family, no life. . . .”

Canadians celebrate their railways, he contends, but don’t fully recognize the heroic achievement of the construction of the Trans-Canada Highway, perhaps the longest fully paved highway in the world. One doesn’t have to confine descriptions of the heroic and the landscapes from which it arises to the Mediterranean world or the Scandinavian coasts of the Viking age.

“The Trans-Canada has never received its due from us. Pratt, Berton, Lightfoot: they all celebrate the train. “There was a time in this fair land. . . .” But what about the highway? To me it is the single most romantic physical accomplishment of Canadians. It runs in 2 lanes, sometimes 4, from Atlantic to Pacific. People driver cars, trucks, vans from one end to the other. It has been crossed by hitchhikers, cyclists, and a runner with one artificial leg. Why don’t we sing its praises? Why doesn’t it make us stop and think and stare?”

Precosky skilfully moves from the mundane and ugly to the sublime and the heroic. Truckstop Nights makes us think about the meaning of work, pain, fatigue and the expanse of the Canadian landscape. I highly recommend this book.

Don Precosky was interviewed by Sheila Peters on the program, Shadow of the Mountain.

http://www.smithersradio.com/program-playlist/shadow-mountain-playlist-01202017