Yukon River of Verse

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge,

I cremated Sam McGee.

The wind across Lake Laberge whispered the story of Sam McGee, a deck-hand and part-time prospector who was cremated in the boiler of the Alice May, a steamer wrecked on the shores of the lake.

Wrecked boats were common for the Klondikers who came hunting their fortune in the gold fields around Dawson City, in the far reaches of the Yukon. The route to the Klondike, used by prospectors like Sam McGee during the gold rush of 1898 started in Dyea just north of Skagway, Alaska. The Canadian Government had imposed a law that each Klondiker had to haul 2000 pounds of provisions over the steep Chilkoot Pass into Canada. The provisions were to keep the prospectors from starving on their way to Dawson. Just over the pass at Bennet Lake, they built any type of vessel that would float and paddled the connecting lakes to the Yukon River.

Lake Laberge, where my husband John and I started our trip was the beginning of the easiest section of the journey. We looked across the lake at the low hills folding into each other, their evergreen foliage dotted with yellow from the alders and red from the willows. The vegetation made it more hospitable than the barren Chilkoot Pass and Bennet Lake.

But the Lake Laberge was treacherous too with sudden winds that caused boats like the Alice May to sink and paddlers to drown although I’ve never heard of any other than Sam McGee being cremated. To be safe from wind, we worked our way along the shore of the lake taking the long way around rather than across to the outflow. There we found the remains of the hull of the Casca, a boat that was thrown ashore during one of the Leberge’s famous storms.

Not far from the Casca were the remnants of an old telegraph line and station. The line, started in the mid 1800’s was intended to link the United States with Europe by running across Canada, Alaska, the Bering Strait and Russia. It was a $3 million project that was never completed because someone figured out how to lay the more efficient transatlantic cable.

The Yukon River is littered with the remains of dead dreams. Each time we stopped to camp or pee, we poked around and found wood piles still waiting to feed the steamers, which burned about two cords of wood an hour at the cost of anywhere between seven and ten bucks a cord. Or we came across the remains of a sod-roof cabin built and used by the latecomers who couldn’t make it up to Dawson before the winter snows arrived and the river froze over.

We entered the Yukon River along with four young men on a homemade raft that got its steam by catching the wind in its sail. We soon left them in our wake.

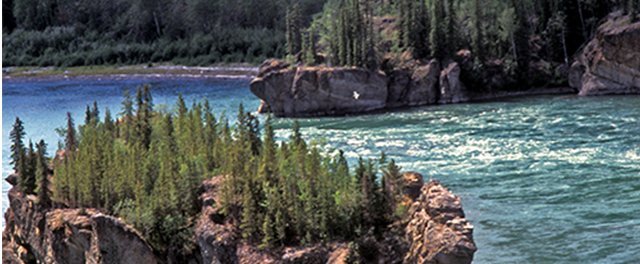

The first 30 miles of the river was narrow, fast and dangerous with boiling rapids, high banks and no eddies to pull into for safety. Service again came to mind.

Beneath us the green tumult churning, above us the cavernous gloom,

Around us, swift twisting and turning, the black, sullen walls of a tomb.

We spun like a chip in a mill race: our hearts hammered under the test.

Then – oh the relief on each chill face! We soured into sunlight and rest.

The river current shoved us through in no time and we had to pull a tight eddy turn to park the canoe beside the riverbank at the village of Hootalinqua. On shore was the roadhouse that once catered to over 100 miners who had worked in the area as early as 1896. Now it catered to our imaginations.

We paddled for a few hours more, camping that night at the confluence of the Big Salmon River. During the gold rush this was another cordwood stop. Now it was a cozy campsite. We tucked in early; me with my tiny volume of Robert Service’s Ballads of a Cheechako, which I could easily read in the light of the midnight sun while John snored contently.

Service had come to the Yukon from Scotland at the age of 22 with five bucks in his pocket and adventure in his heart. He worked for the Bank of Commerce and in 1902 was sent to the Yukon. For him it was one of those fortunate chances of history. Although he had missed the gold rush when Dawson’s population had swollen to 40,000, he was able to get the flavour of the era from old timers who still spent five months a year prospecting on the creeks around Dawson City.

Our next stop was Carmacks a pit stop where the Alaska Highway bridges the Yukon River. From shore we could see a tent-city campground and canoes stacked like cordwood indicating that other paddlers wanted the luxury of civilization before pushing on to Dawson, another week away.

About five years before the gold rush, George Carmack built cabins near the present day town site in the hope of mining coal in the area. However his explorations up and down the river led him to Bonanza Creek where he discovered gold and started the whole dammed rush.

We ate hamburgers and drank cold beer and talked with other paddlers about the Five Finger Rapids that waited a few kilometers downriver. Named as such because of the five channels that run between four basalt columns, the rapids have high standing waves, which have capsized more than one boat and taken many lives. There is a rumour that during the gold rush, a net was placed below the rapids so as to catch the corpses before they went all the way down to the Bering Sea. Survivors were supposed to dig graves for their dead companions.

We lined up our canoe to run the rapids. My adrenalin rushed at the same speed as the current. Paddles gripped tight, we bounced and churned over the waters and were through in what to me seemed like a blink. And we didn’t have to stop to dig any graves. Service again came to mind;

But what of the others that followed, losing their boats by the score?

Well could we see them and hear them, strung down that desolate shore.

What of the poor souls that perished? Little of them shall be said

On to the Golden Valley, pause not to bury the dead.

Down river a layer of volcanic ash lined the shore. The ash came from a volcanic eruption in the Wrangle-St Elias Mountains before the birth of Christ. The landmark is affectionately called Sam McGee’s ashes. An enterprising officer on the Yukon Steamer Klondike was known to take gullible passengers aside and offer them a bottle containing some of Sam McGee’s ashes. The ashes were cheap as long as the customer said nothing about it, and in the end the officer ended up with more money than most prospectors.

The following two days paddling we passed the remains of many steamers sticking partly above the water, a cold reminder to take caution no matter how mellow the river seemed. Our next stop was Fort Selkirk at the mouth of the Pelly River. We slid gently onto shore and hauled our gear up the steep incline to the campsite. The sun glistened off the restored wooden buildings giving them a welcoming warmth.

Robert Campbell, a Hudson’s Bay Company explorer, was the first white person to paddle the Pelly into the Yukon River. In 1848 Campbell established a fort and called it Ft. Selkirk. By the time the gold miners were coming through, the area was inhabited by over 200 people and serviced by a trading post, a school, a mission house and steamers brought in supplies. In 1899 a post office was built and the North West Mounted Police established a post in an attempt to keep rein on the unruly Klondikers. Now they keep rein on the paddlers!

Our final destination was just two days away. When we floated toward the town dock of Dawson City I heard the words of Service describing the scene from over a century ago:

There were the tents of Dawson, there the scar of the slide;

Swiftly we poled o’er the shallows, swiftly leapt o’er the side.

Fires fringed the mouth of Bonanza; sunset filled the dome;

The test of the trail was over – thank God, thank God, we were home!

The scar of the slide was there and the mouth of Bonanza Creek. But instead of tents we saw motorhomes and instead of fires we saw bars. However, with aching shoulders and growling stomachs, we felt the same as the early prospectors. “The test of the trail was over – thank God, thank God we were home!”

Quotes taken from “The Cremation of Sam McGee” and “The Trail of the ’98.”

The story was first published in Above & Beyond Magazine, May/June 2000